We just published a paper on fast remote z-scanning using a voice coil motor. For 2P calcium imaging. It’s a nice paper with some interesting technical details.

The starting point was the remote z-scanning scheme used by Botcherby et al. (2012) from Tony Wilson’s lab, but we modified the setup to make it easier to implement for an existing standard 2P microscope, and we used only off-the-shelf components, for in total <2500 Eur.

The first challenge when implementing the Tony Wilson remote scanning scheme was to find something that can move a mirror in axial direction with high speed (sawtooth, >5 Hz). Botcherby et al. used a costum-built system consisting of a metal band glued to synchronized galvos. In order to simplify things (for details on optics etc, see the paper), I was looking for a device that comes off-the-shelf and that can move fast in a linear way over a couple of millimeters. That is, a very fast linear motor. Typical linear motors are way too slow (think of a typical slow microscope stage motor).

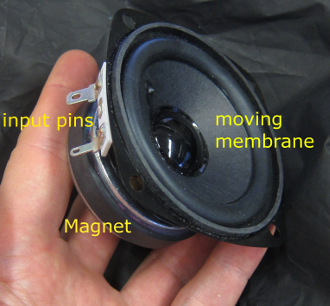

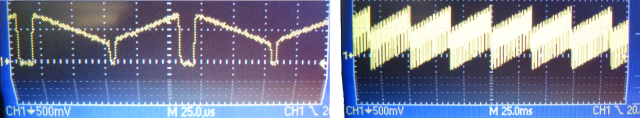

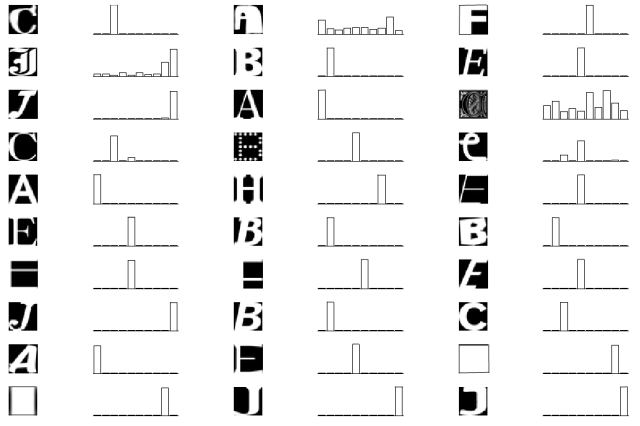

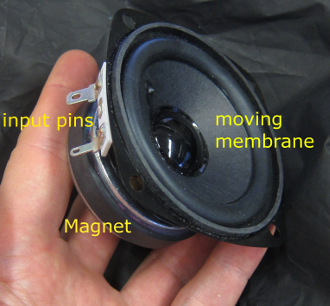

End of 2014, I found a candidate for such a linear motor: loudspeakers. When you have a close look at large subwoofers, you can see that the membranes move over many millimeters in extreme cases; and such loudspeakers are used for operation between 20 Hz and 10 kHz, so they are definitely fast. So I bought a simple loudspeaker for 8 Euro and glued a mirror onto the membrane. However, precision in the very low frequency domain (< 50 Hz) was limited, at least for the model I had bought:

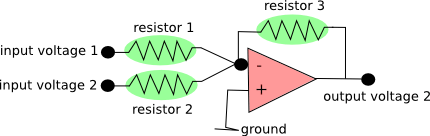

But as you can see, this is a very simple device: A permanent magnet and two voltage input pins, nothing else. Ok, there is the coil that is attached to the backside of the membrane, but it remains very simple. The copper coil is permeated by magnetic field and therefore experiences a force when electrical current flows through the coil, thereby inducing motion of the coil and the attached membrane.

In spring 2015, I realized that the working principle of such loudspeakers is called “moving coil” or ” voice coil”, and using this search term I found some suppliers of voice coil motors for industrial applications. These applications range from high repeatability positioning devices (such as old-fashioned, non-SSD hard drives) to linear motors working at >1000 Hz with high force to mill a metal surface very smoothly.

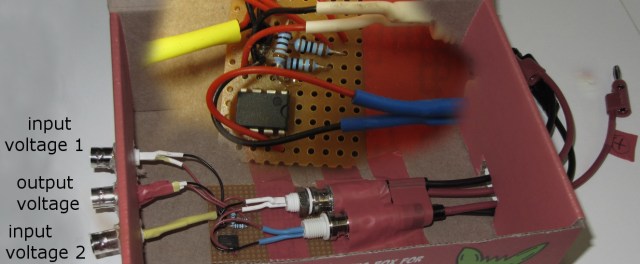

So, after digging through some company websites, I bought such a voice coil motor together with a servo driver and tried out the wiring, the control and so on. It turned out to be such a robust device that it is almost impossible to destroy it. I was delighted to see this, since I knew how sensitive piezos can be e.g. when you push or pull into a direction that does not convene to the growth direction of the piezo crystal.

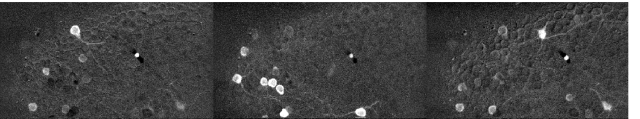

This is how the voice coil motor movement looks like in reality inside of the setup. I didn’t want to disassemble the setup, so it is here within the microscope. To make the movements visible for the eye, it is scanning very slowly (3 Hz). On top of the voice coil motor, I’ve glued the position hall sensor (ca. 100 Euro). I actually used tape and wires to fix the positions sensor – low-tech for high-precision results.

The large movement of the attached mirror is de-magnified to small movements of the focus in the sample, thereby reducing any positional noise of the voice coil motor. This is also the reason why I didn’t care so much about fixing the hall sensor in a more professional way.

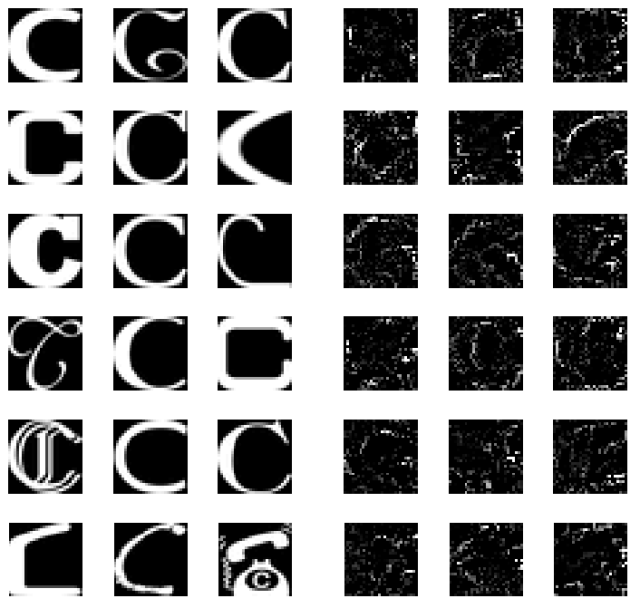

After realizing that it is possible to control the voice coil motor with the desired precision, repeatability and speed, it remained to consider more closely the optics of the remote scanning system. Actually, more than two third of the time that I spent for this paper were related to linear ABCD optics calculations, PSF measurements and other tests of several different optical configurations, rather than being related to the voice coil motor itself.

More generally, I think that voice coil motors could be interesting devices for a lot of positioning tasks in microscopy. The only problem: To my knowledge, typical providers of voice coil motors have rather industrial applications in mind, which reduces the accessibility of the technique for a normal research lab. A big producer of voice coil motors is SMAC, but they seem to have customers that want to buy some thousand pieces for an industrial assembly line. I prefered both the customer support and the website of Geeplus and I bought my voice coil motor from this company – my recommendation.

As described in the paper, I used an externally attached simple position sensor system, but there are voice coil motor systems that have an integrated encoder. Companies that sell such integrated systems are Akribis Systems and Equipsolution, and our lab plans to have a try with those (mainly because of curiosity). Those solutions use optical position sensors with encoders instead of a mechanical hall sensors, increasing precision and lowering the moving mass, but also at higher cost.

One problem with some of these companies is that they are – different from Thorlabs or similar providers – not targeted towards researchers, and I found it sometimes difficult or impossible to get the information I needed (e.g. step response time etc.). If I were to go for a voice coil motor project without previous experience, I would either go the hard way and just buy one motor plus driver that look fine (together, this can easily be <1000 Euro, that is, not much) and try out; or stick to the solution I provided in the paper and use it as a starting point; or ask an electrical engineer who knows his job to look through some data sheets and select the voice coil motor that you want to have for you. I did it the hard way, and it worked out for me in a very short time. Me = physics degree, but not so much into electronics. I hope this encourages others to try out similar projects themselves!

During the review process of the paper, one of the reviewers pointed out a small recent paper that actually uses a regular loudspeaker for a similar task (field shaping). This task required only smaller linear movements, but it’s still interesting to see that the original idea of using a loudspeaker can somehow work.

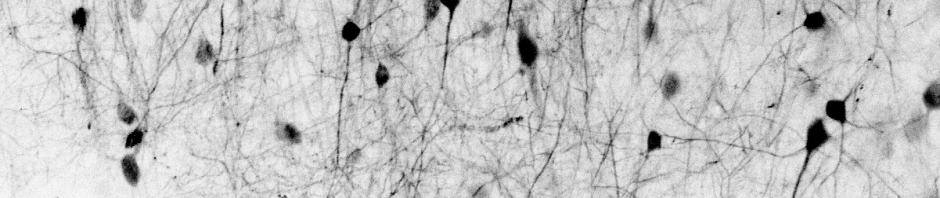

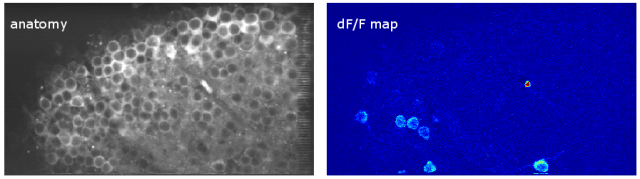

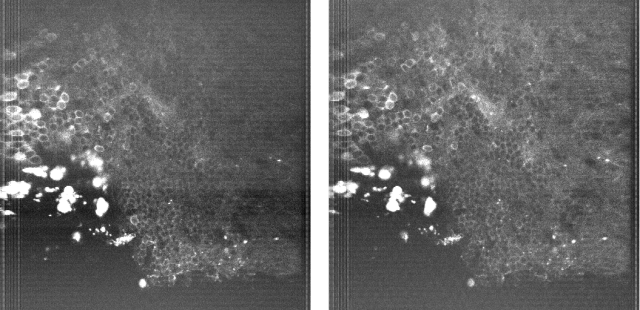

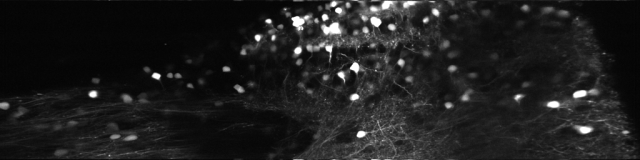

Since then, I’ve been using the voice coil motor routinely for 3D calcium imaging in adult zebrafish. Here is just a random example of a very small volume, somewhere in a GCamped brain, responding to odor stimuli. Five 512 x 256 planes scanned at 10 Hz. The movie is not raw data, but smoothed in time. The movies selected for the paper are of course nicer, and the paper is also open access, so check it out.