How does the brain work, and how can we understand it? To approach this big question from a broad perspective, I want to report on some ideas about the brain that marked me most over the past twelve months and that, on the other hand, do not overlap too much with my own research focus. Enjoy the read! And check out previous year-end write-ups: 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024.

For this year’s wrap-up, I reflect on what it would mean to achieve experimental goals that currently seem out of reach.

This is part III, with part I and part II online already.

III. Simultaneously recording from all neurons of the human brain

The idea:

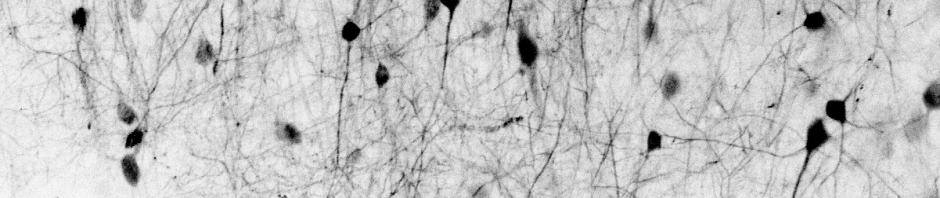

Since the middle of the last century, the number of neurons recorded simultaneously in animal brains has steadily increased (Urai et al., 2022). Around the year 2000, it became clear that simultaneously recording multiple neurons provides insights into the brain that could never be obtained from single neurons alone. More than 20 years later, these population dynamics remain an active and important area of research. For this reason, recording from all neurons is often described as the ultimate thought experiment: first in a simple organism like C. elegans (Randi and Leifer, 2020), then in a vertebrate like the zebrafish larva (Ahrens et al., 2013), a mammal like the mouse, and eventually in humans, with their roughly 80 billion neurons.

Why it won’t work:

At present, no method comes even close to achieving this goal. With fMRI, it is never entirely clear what signals are actually being measured. In addition, both the temporal resolution (approx. 1 s) and spatial resolution (approx. 1 mm) are far from what would be required (0.001-0.01 s temporally, <0.01 mm spatially).

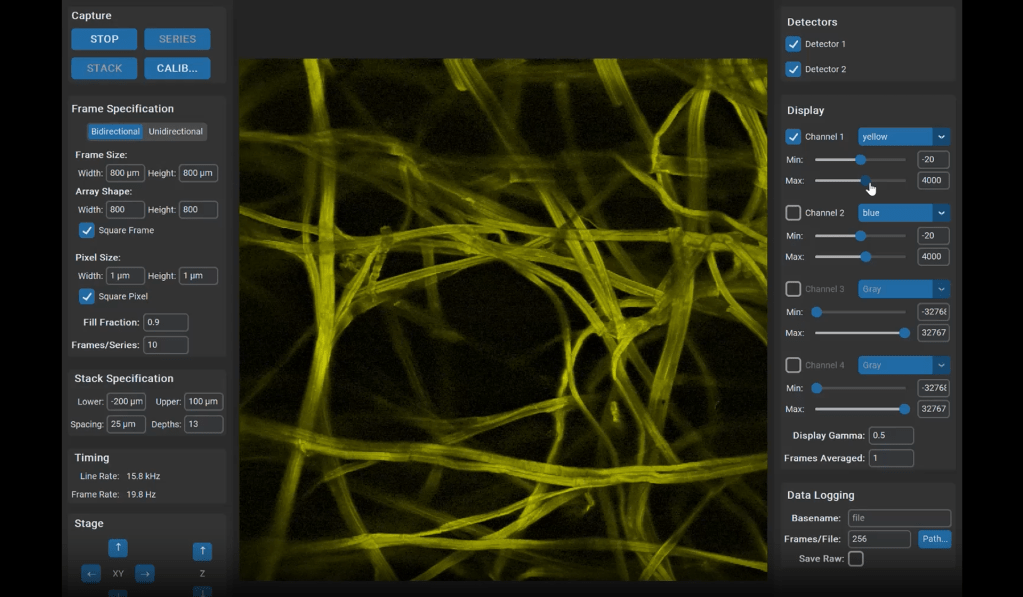

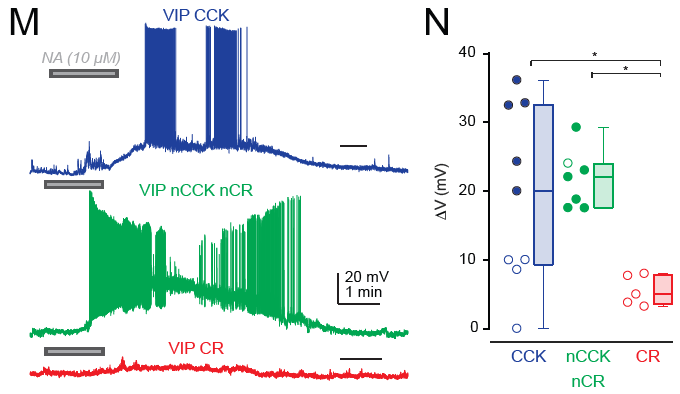

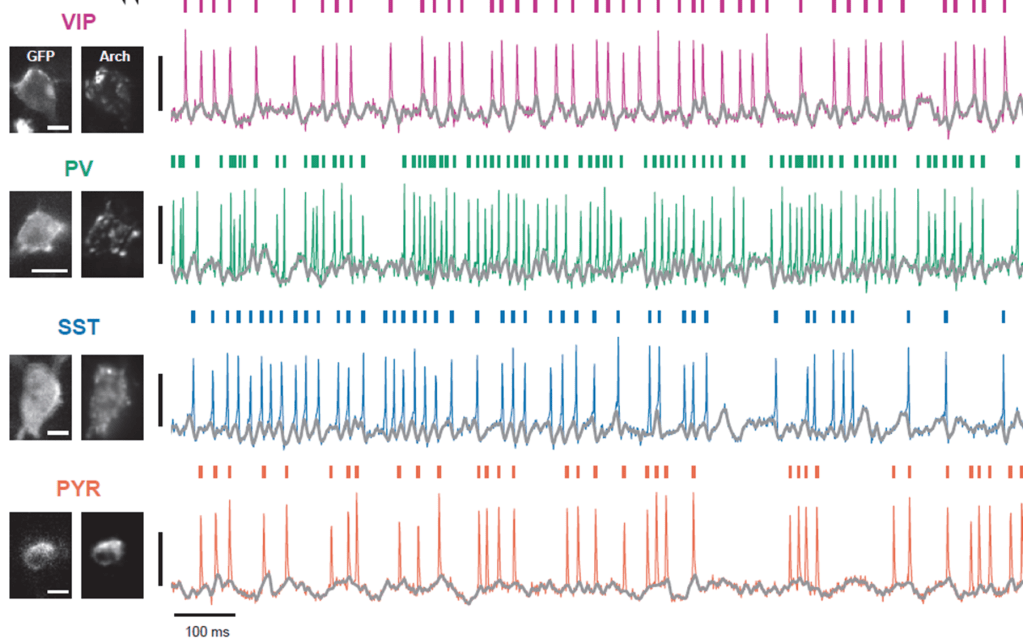

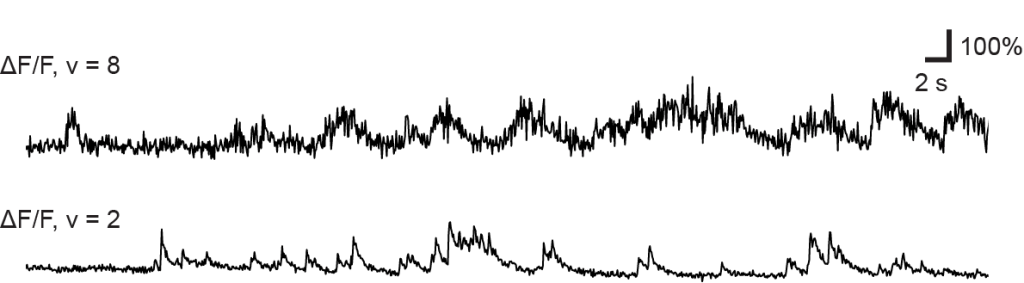

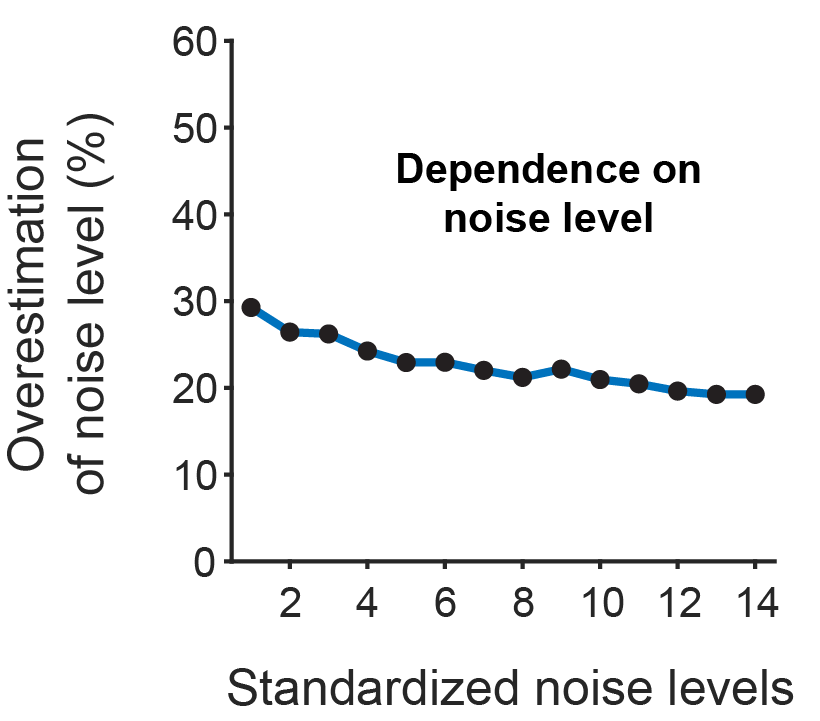

Optical microscopy can record from thousands – and in extreme cases up to a million (Demas et al., 2021) – cells in animals, but this number comes at the cost of temporal resolution and yields only an indirect and noisy proxy of neuronal activity.

In contrast to optical cellular microscopy, electrophysiology is used in humans as well, but at most from some thousand cells – roughly 0.00000001% of all neurons. Moreover, every electrophysiological method destroys more neurons than it records, reflected in the Butcher number introduced by Markus Meister. This problem becomes worse the farther one moves away from the cortex, toward the hypothalamus or small nuclei in the deep brainstem, or to neurons hiding close to the walls of the ventricles. Every method is invasive in its own way, and none is truly scalable, despite claims to the contrary.

Perhaps, someday there will be methods by which neurons are programmed to send, in addition to their actual axon, a collateral branch to the brain surface, where the axon as the “key” finds a genetically programmed “lock” attached to an electrode that allows recording from this biological axon. With such a design, invasive methods would no longer be necessary because the signals would present themselves on a silver plate. For these 80 billion additional axons, one would merely need to find about half a liter of extra space inside the skull and develop readout electronics capable of listening to a single axon within an area of roughly 1 µm² and forwarding the signal to a recording device. Let us not look too closely into further, even less comfortable details, such as the cables dangling from the head and data storage: 80 billion × 1,000 Hz data points per second – this is roughly 80 terabytes of data per second, assuming 8 bit signals – would challenge even the most advanced streaming and storage technology.

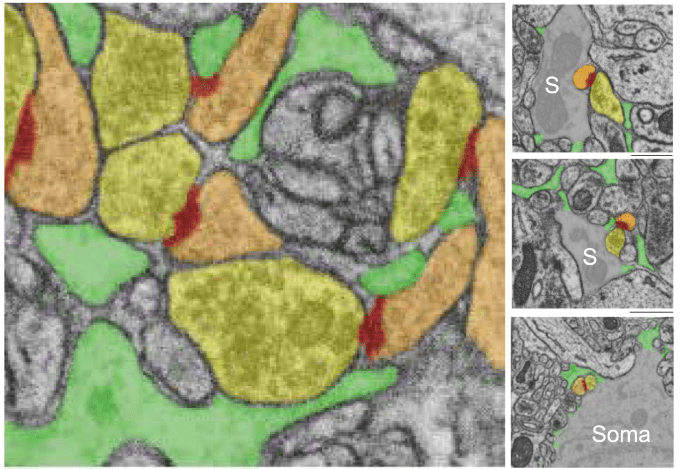

And what would still be missing is, of course, the subcellular and subthreshold state of each neuron: its membrane potential across soma and dendritic structure, as well as plastic cellular and synaptic dynamics on short timescales (facilitation, adaptation) and long timescales (LTP, LTD, immediate early genes, etc.). At present, there is no even remotely scalable approach to collecting such data in any animal, not to speak of humans.

What we would learn:

Suppose we had this dataset in front of us: 80 billion cells, recorded for 24 hours, with every action potential detected. Let us ignore the cerebellum for the moment, with its 60 billion neurons, leaving “only” 20 billion. Assuming an average firing rate of 0.1 Hz (the true rate, including interneurons, is likely somewhat higher), we would observe roughly 2 million action potentials every millisecond.

One of the most fascinating aspects would be to see how action potential patterns propagate and how they correspond to thoughts and sensory impressions. If, for example, the subject watched a movie during recording, or if he or she imagined navigating through a space, spoke words, or was suddenly startled, we could follow the activity patterns through the brain from one region to another as they spread, persist, and eventually fade. We could examine how stable these activation patterns are, how widespread they are, and whether they are distributed or localized. We could reconstruct reaction times to sensory stimuli across all brain regions.

We could focus on a specific brain region – let’s say, the arousal center of the locus coeruleus or the dopaminergic substantia nigra pars compacta – and quantify, for every neuron in the brain, how its activity is influenced by this specific neuromodulatory nucleus.

If the dataset was good enough, perturbations would no longer be necessary to study causality of synaptic interactions; observation alone could yield enormous insight.

What I find most appealing about this thought experiment is the ability to trace a thought as it moves through the brain. Would it resemble videos of bird flocks, seemingly chaotic yet tightly coordinated by local interactions? Or would it look more like completely distributed, spatially disconnected activity patterns? It is clear that such dynamics are at least partially chaotic, that is, that the dynamics will strongly depend on initial conditions (the state of the network before a repeatable event such as a sensory stimulus). If we could record all neuronal activity, we might even be able to predict such less organized and more chaotic dynamics and understand how chaotic and “critical” neuronal activity really is.

These are very general ideas, but once you think more concretely about already known phenomena of neuronal activity, many additional exciting questions emerge. How are sharp-wave ripples triggered, from cortex to thalamic or brainstem nuclei? Where does the activity of dopaminergic neurons, whose signals are still debated in terms of reward prediction errors versus movement signals, originate? A systematic screen of activity across all brain regions could clarify exactly such questions and put theories, often built on tiny slices of neuronal activity and behavior, to a serious test.

Overall, I don’t think that an understanding of the brain would suddenly appear once we have this dataset; we would not understand the nature of consciousness, and would not be able to recreate the brain; but many existing research fields would be pushed forward, and many existing questions of basic research would be answered immediately.

References

Ahrens, M.B., Orger, M.B., Robson, D.N., Li, J.M., Keller, P.J., 2013. Whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution using light-sheet microscopy. Nat Methods 10, 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2434

Demas, J., Manley, J., Tejera, F., Barber, K., Kim, H., Traub, F.M., Chen, B., Vaziri, A., 2021. High-speed, cortex-wide volumetric recording of neuroactivity at cellular resolution using light beads microscopy. Nat Methods 18, 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01239-8

Randi, F., Leifer, A.M., 2020. Measuring and modeling whole-brain neural dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 65, 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2020.11.001

Urai, A.E., Doiron, B., Leifer, A.M., Churchland, A.K., 2022. Large-scale neural recordings call for new insights to link brain and behavior. Nat Neurosci 25, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00980-9