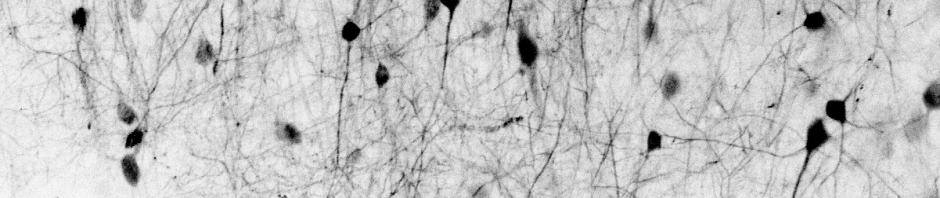

Clouds, seen from above. © The author, 2015.

When thinking about the way we think, it certainly makes sense to begin with a point which is also used by our thoughts as a starting point, which is sensual experience. To give an example, it is easy to imagine how a visual experience is categorized and analyzed over several cortical stations in more and more complex and fine representations, up to a representation of e.g. a human person in the infero-temporal (IT) cortex of the ventral path of visual information processing. This high-level representation could be done by a single neuron – although this seems unlikely, so let’s say rather the representation consists of a cluster of neurons.

But hold on. I can image that this [cluster of] neuron[s] becomes active for the task of the sensual-passive categorization of this person. But how could the reverse order be accomplished, going from the pure activation of this neuron to the vivid internal imagination of the person? When I think of my brother (i.e. activating the assumed neuron that represents my brother), sensual-like impressions and memories will quickly come to my mind, which I can follow and deepen to a rather arbitrary extent. Where does this come from?

I would naively assume that the bare activity of a neuron in my inferotemporal cortex has nothing sensual, not more than a charging and de-charging condensator in an electrical circuit (given that neurons use a code as simple as most people suppose). To me, the most obvious way how sensuality could enter the game, is the same way it came there in the first place when it helped to generate the concept of this person – only that this path would have to be walked in the opposite direction in the hierarchy of the cortical architecture of the visual system, thereby reconstructing the individual components of the visual percept which might be located in V1. – If we pursue this line of thought, this means that processing paths which have once been developed and strengthened by sensual experience would have to build in at the same time a way back, in order to allow the concept to go back from the high-level presentation to the low-level sensual components at a later point in time. – Two problems are evident at this point: First, from biological intuition, you would not expect the formation of exact reciprocal connections to arise, since neurons are by construction processing units that tend to operate unidirectionally. Second, this concept would lead to a circular way of signal processing. It’s like having a lot of pointers which are pointing to other pointers, but without anything real at which they point to in the end. Still, a pointer to V1, an unconsciously existing neuronal layer close to perception, seems to be rather better equipped with sensuality than a pointer to any other meaningless empty neuron in IT. I’m sure that people in 200 years will laugh about this tentative attempts to think about representations in the brain, but I would like to meet the woman or man who is in a position to do this now …

In the space of the subjective consciousness, this process is much easier to imagine and to describe. From an abstract term that I am told by a stranger, like the name of my brother, or maybe the expression ‘cumulo-nimbus clouds’, automatically a vivid image of this cloud formation arises; but I could also reject and suppress this imagination; or I could deliberately pursue this picture, searching my memories, rendering them more concrete and sensual with every second I spend thinking about them; maybe even taking a piece of paper to draw a physical picture of the image in my head. Therefore, in any case, this supposed reciprocal connection would not be a purely self-acting cascade back to the original sensual representation, triggered by the activation of a higher-level neuronal representation, but a loose option and subthreshold activation which I can pursue further by the the reinforcing focus of my attention, but which I cannot follow to any imaginable level of detail – at the latest when trying to draw the cloud, I would realize that I do not exactly know how this clouds (or clouds in general) look like in reality and that I can recall nothing but a vague impression. Translated to the idea of reciprocal connections for recall of sensuality, these reciprocal connections would be asymmetric, and the forward image would certainly be not invertible, or only in the vague approximation that I can also experience when recalling the shape of a cumulo-nimbus cloud.

Of course, even if this concept were true, it would be only a part of what is happening in the brain. Beside the sensual recall, also the emotional valence comes into play, which is unlikely to be coded by sensory pathways. Plus, other abstract associations and memories will occur, like the recall of the cloud picture on top of this post at the moment I mentioned cumulus clouds further below. Those associations, however, in turn might each of them cast a vague sensual shadow in the earlier sensory layers …

What I like about this concept is the use of pointers. There is a slight, but maybe interesting difference between thinking of the brain network as an associative network and as a network of pointers. In an associative network, it is objects or representations that are linked to each other; in a network of pointers, single objects do not have a meaning, and only the location or address where they are pointing to makes them meaningful. The second description, different from the ‘associative network’ description, immediately triggers the question: Where, during recall, does the accompanying sensual experience come from?