There is no recipe for discoveries, and there is no cookbook on how to publish a paper. But at least there are typical events and routes that are often encountered. Here, I’d like to share the trajectory of a study that we recently published in Nature Neuroscience (Rupprecht et al., 2024), with the hope that my recount will be useful for those who have a similar path before them and especially for those who may encounter these obstacles for the first time.

Conceiving a research project

When I joined the lab of Fritjof Helmchen at the University of Zurich in Summer of 2019, I was primarily interested in the role of pyramidal dendrites, and I was hoping to work on dendritic calcium imaging for my postdoc. However, at very short notice, Fritjof was looking for somebody to shoulder a project focused on calcium signals in hippocampal astrocytes, and he managed to convince me to give it a shot. At this point, we had a clear hypothesis (derived from the slice experiments of a PhD student), and I thought this could be a mini-project to get me started working with mice: doing my first surgeries, building a 2P microscope, and building my first behavioral rig.

The first technical problems

The initial plan was to perform calcium imaging of pyramidal neurons and astrocytes in hippocampus of mice on a treadmill. The treadmill design I copied from the then-junior research group of Anna-Sophia Wahl and learned from her and other researchers how to implant a chronical window that enables to look into the hippocampus of living mice. However, I soon struggled with the first major problems.

First, in an attempt to perform dual-color imaging of astrocytes and neurons, I injected two viruses. One to express the red calcium indicator R-CaMP1.07 in neurons, the second to express the green calcium indicator GCaMP6s in astrocytes. To be sure, I replicated the procedures from a neighboring lab that had used this very same approach in cortex (Stobart et al., 2018). However, my attempts were not successful. I could express either R-CaMP in neurons or GCaMP in astrocytes, but not at the same time. It seemed like a mutual exclusion pattern, due to phase separation or some sort of competition among the viruses. I learned that this has happened to others as well, but nobody seems to fully understand under which conditions it does so. In any case, I gave up on dual-color imaging and simply performed calcium imaging of astrocytes to get started.

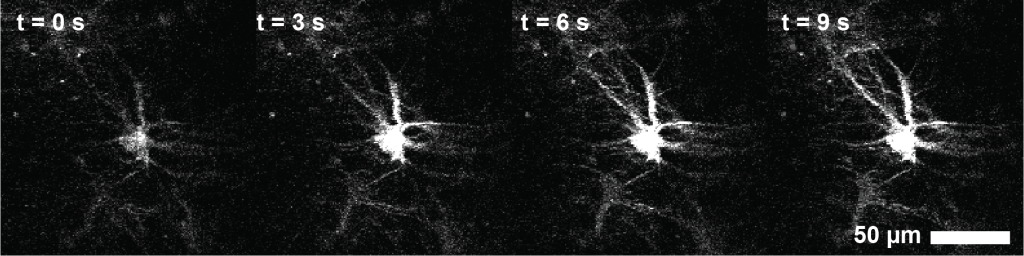

A second, more severe problem was my struggle with the interpretation of the observed calcium signals. The calcium signals were extremely weak and dim, and astrocytes only become vaguely brighter during activity. I therefore focused on the only astrocytes that I could see, the very superficial ones. This turned out to be a mistake. After my first surgeries – and I waited only little before performing imaging experiments – there was a thin layer of reactive astrocytes at the surface between hippocampus or corpus callosum and the cover slip. These astrocytes were not only a bit larger than normal astrocytes, but also brighter, and responsive towards slightly increased laser power (Figure 1).

After several months of confusion and iterations, I suspected and confirmed that these astrocytes were activated not by behavioral circumstances but by the infrared imaging laser. I then improved my surgeries and focused the imaging on the deeper and much dimmer normal hippocampal astrocytes. But I remained suspicious about reactive astrocytes.

Lockdown / Covid-19

In March 2020, I had my first cohort of mice with nicely expressing astrocytes (in particular non-reactive astrocytes!). I had recently improved my microscope in terms of collection optics, resolution and pulse dispersion. First tests under anesthesia were promising, and I was starting to habituate the animals to running on the treadmill. I was about to generate my first useful dataset! Then, Covid-19 hit me. The Brain Research Institute, as all of the University of Zurich, was locked down, and I had to euthanize my mice and terminate the experiments. I went into home office and, not having acquired any useful data yet, worked on the analysis of existing data for other, independent projects that I expanded instead (Rupprecht et al., 2021).

In Autumn 2020, finally, I again prepared a cohort of animals, verified proper expression in astrocytes, and recorded my first dataset of mice running on a treadmill, while recording body movement and running speed. At this point, it was already quite clear that my data did not contain any evidence to support the initial hypothesis that I had used as a starting point. So the project switched from hypothesis-driven to exploratory.

Looking at the data

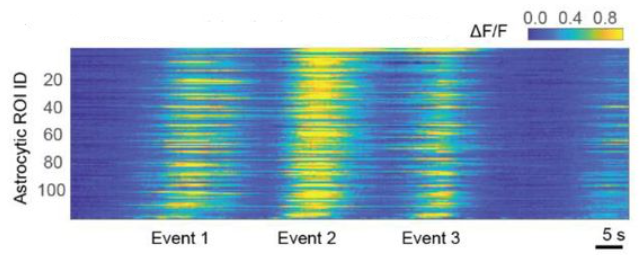

My first decent recordings of astrocytes with calcium imaging were incomprehensible to me at first glance, and drowning in shot noise. The activity did no obviously correlate with behavior, at least from what I could tell when watching it live. I was a bit lost. One of the main problems I struggled with was the efficient inspection of raw data. Finally, I spent two days and wrote a Python-based script to browse through the raw data (not much in hindsight, but very useful to advance the project). To this end, I synchronized calcium data, behavioral videos of the mouse, and behavioral events such as sugar water rewards, spatial position or auditory cues. Then I carefully browsed through the data, something like 20-30 imaging sessions of each roughly 15 minutes with very variable recording quality. It took me roughly two weeks of focused work (Figure 2). I noticed that the random spontaneous activity of individual astrocytes did not correlate with anything. From the single trials where I found a correlation, I tried to build different hypotheses, but none of them could hold up to a critical test with the rest of the data. The only thing which was more or less consistent was an almost simultaneous activation of most astrocytes throughout the field of view.

Figure 2. Annotations of recordings after visual inspection of calcium recordings together with behavioral movies. In total, I took around six pages of such notes.

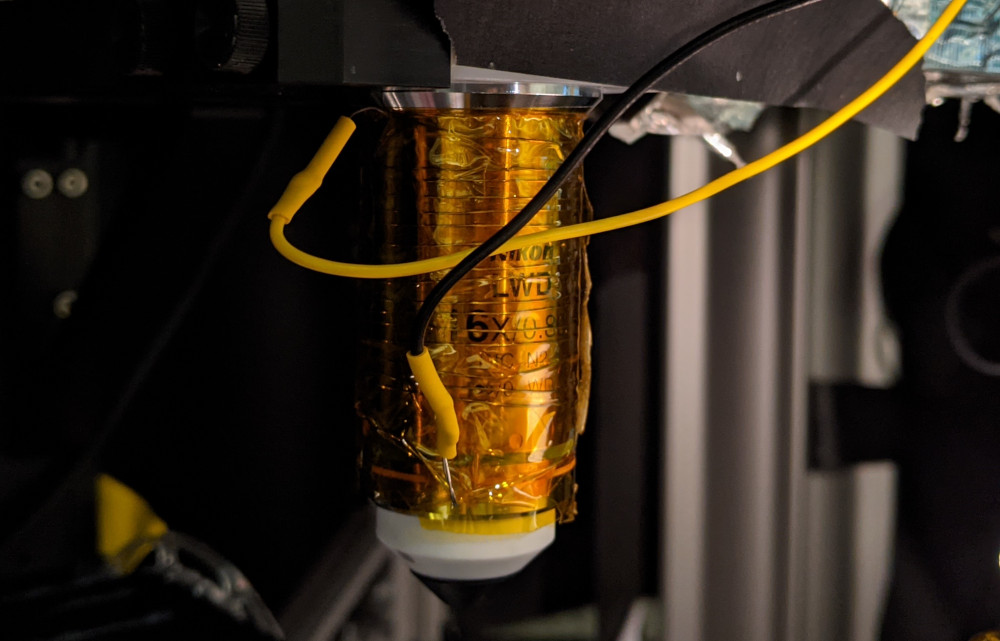

Given my bad experience with laser-induced activation of reactive superficial astrocytes, I was worried rather than happy. Was there an effect of switching on the laser, which lead to a global activation of astrocytes due to accumulation of heat? I spent a few months investigating this artifact. I reasoned that these activations might be due to laser-induced heating, as described for slices (Schmidt and Oheim, 2020). So I warmed up the objective with a custom-designed objective heater (Figure 3). However, I did not observe astrocytic activation through heating. Together with more experiments, I started to believe that what I was seeing was real.

Another thing I noticed that often the animal, whether it was moving or not, seemed to be quite aroused approximately 10 seconds before these activation patterns. This was difficult to judge and only based on my visual impression of the mouse. From these rather subjective impressions, I drew the conclusion to definitely monitor pupil diameter as a readout of arousal for my next batch of animals – which turned out to be essential for the further course of this project.

In hindsight, these observations seem pretty obvious. While I struggled with the conceptualization of the data, similar results and very clear interpretations were already in the literature, and not too well-hidden (Ding et al., 2013; Nimmerjahn et al., 2009; Paukert et al., 2014). The only problem: I did not know about them. I was definitely reading a lot of papers on astrocytes – but still driven by my initial hypothesis, which was focused on a slightly different subfield of astrocyte science that was somehow not connected at all to this other field of astrocyte science. Only several months later, when I had confirmed my own results, I noticed that some of these results were already established, in particular the connection of astrocyte activation with arousal and neuromodulation.

First results

A key decision for the progress of this project was to drop all analyses of single-cell analyses for the moment. For a long time, I had been trying to find behavioral correlates for single astrocytes that were distinct from the global activity patterns, but I was unable to find anything robust. The main problem was that astrocytic activity is very slow. As a consequence, a single astrocyte will sample only a very small fraction of its activity space during a typical recording of 15 to 30 min. This feature makes it challenging to find any robust relationship with a fast-varying behavioral variable.

Therefore, I started analyzing the mean activity across all astrocytes in a field of view. This part of my analyses is now reflected in the figures 2-4 in the paper (Rupprecht et al., 2024) in its current form.

After more in-depth analysis, validation and literature research, I still found these systematic analyses of the relationship between astrocytic activity and the behavior or neuronal activity quite interesting and relevant. At the same time, I also realized that much of these findings had already been made before: often in cortical astrocytes (Paukert et al., 2014), but partially also in Bergmann glia in cerebellum (Nimmerjahn et al., 2009), although not in hippocampus. Nowhere, however, the description seemed as systematic and complete as in my case. So I thought this could make a good case for a small study of somewhat limited novelty but with solid and beautiful descriptive work. I also felt that recently published work on hippocampal astrocytes made misleading interpretations about the role of hippocampal astrocytes (Doron et al., 2022), an error that was easy to identify with my systematic analyses. So I started to make first drafts of figures.

A bold hypothesis

In Summer 2021, I had an interesting video call with Manuel Schottdorf, then located in Princeton and working in the labs of David Tank and Carlos Brody. Among other things, we discussed about the role and purpose of hippocampus. Specifically, we discussed about the hippocampus as a sequence generator. I can see this discussion topic tracing back to the work on “time cells” by Howard Eichenbaum (Eichenbaum, 2014), but also to work from David Tank’s lab (Aronov et al., 2017). The potential connections of such sequences to theta cycles, theta phase shifting, replay events and reversed replay sequences seemed complicated and still opaque, but also highly interesting. I left the discussion with new enthusiasm about studying the function of hippocampus.

A few days later, I went back to the analysis of astrocytic calcium imaging data from hippocampus, and to the analysis of single-cell activity. Out of curiosity, I checked for sequential activity patterns by sorting the traces according to their peaks. Indeed, I found a clear sequential activation pattern across astrocytes (Figure 4).

I expected this effect to be an artifact that can occur when sorting random, slowly varying signals and performed cross-validation (sorting on the first part of the recording, visualization on the second half), but the sequential pattern remained. I was a bit puzzled (why should astrocytes tile time in a sequence?), but also a bit excited. I went on to analyze recordings across multiple days and observed that the same astrocytes seemed to be active in the same sequences across days. Intriguing! This was a very unexpected finding. And, as most findings that are unexpected and surprising, it was wrong. But I was still excited and set up a meeting with my postdoc supervisor Fritjof to discuss the data and analyses.

Death of a hypothesis, birth of a new hypothesis

The evening before the planned meeting, I was questioning the results and performed further control analyses. For example, I specifically looked at astrocytes that were activated early in the sequences and those that were activated later. Was there any difference? I could see none.

I checked whether there was any spatial clustering of astrocytes that were temporally close in a sequence, but this did not seem to be the case. Finally, already late during the evening, I wondered whether sequences could be subcellular instead of across cells, for example always going from one branch of an astrocyte to another branch. To test this alternative hypothesis systematically, I came up with the idea to test the sequence timing on a single-pixel basis. Single pixel traces were quite noisy, but it was quite clear to me correlation functions would solve this problem (only a few years before this time, I had written even a blog post on the amazing power of correlation functions!). So, I used correlation functions to determine for each pixel in the FOV whether it was early or late in the sequence, using the average across the FOV as a reference. It took me an hour to write the code, and I let it run over night over a few datasets. In the morning (as the next paragraph will show, I’m definitely not a morning person), I looked at the results, and at first glance I could not really see a pattern (Figure 5). In some way, I was relieved, because this was only a control analysis. I quickly made a short set of power point slides ready and went to work.

Fritjof was quick as usual to understand all the details of my analyses and controls. He was intrigued, but with a good amount of scepticism as well (and I was still very sceptical myself). However, when I showed the results of the pixel-wise correlation function analysis, telling him that I did not see a pattern, he looked carefully and was a bit confused.

He clearly saw the pattern: somatic regions of astrocytes were activated later, while distal regions were activated earlier. It took me several seconds to acknowledge that this was indeed true. Why had I not seen it myself? Maybe because the colormap that I used was not a great fit for my colorblind eyes; or because I had not slept a lot before looking at the data; or because I had introduced a small coding error that shifted these delay maps compared to the anatomy maps. A bit confused, I promised to look very carefully into this observation. And every analysis I did afterwards confirmed it. That’s how we made the central observation of our study – centripetal propagation. At this point, I was not yet fully convinced that this would be an important finding; interesting, for sure, but not necessarily the key to understanding astrocytes. I changed my mind, but only gradually.

Writing up a first paper draft

End of 2021, I decided to write everything up for a paper: a solid and descriptive piece of work: No fancy optogenetics, no messy pharmacology, no advanced behavior or learning, just a solid paper.

Often times, my writing and analysis is an entangled process that can take months if it requires complex analyses and a lot of thinking. In this process, I found two additional interesting aspects about centripetal propagation that I had missed before. I noticed that sometimes propagation towards the soma seemed to start in the periphery of the astrocyte, only to fade out before reaching the soma. Very quickly, I realized that these fading events occured primarily when the arousal, as measured by pupil diameter, was low. I took me a bit more time to understand the relevance of this finding: Arousal seemed to control whether centripetal propagation occured or not.

The more I thought about it, the more I found it interesting. I had always been fond of dendritic integration mechanisms and how apical input to pyramidal cells gated certain events like bursts (Larkum, 2013). Here, I saw a similar effect at work, with somatic integration in astrocytes being gated by arousal.

Submitting the manuscript

After a few iterations with my postdoc supervisor Fritjof, we finished a first version of the manuscript. I presented the data at FENS in Paris in Summer 2022 and received positive feedback. Briefly after that, we submitted the manuscript to Cell. I’m rather hesitant to submit to the CNS triad (the journals Cell/Nature/Science). However, in this case I thought that the story of conditional somatic integration in astrostrytes was so interesting that it did not need to be stretched and massaged in order to be fascinating for a broader audience. We selected Cell because they accept papers with a larger number of figures. After a reasonable amount of time, we got an editorial rejection, with an helpful explanation of why they did not consider the paper; I was a bit disappointed but was positively surprised by the editor who provided some helpful feedback. We transfered the manuscript to Neuron, which would in my opinion have been a perfect fit for the paper due to manuscripts of related topics in the same journal in the past, but it got rejected with a standard reply. Quite disappointing! I decided to give it another try, with Nature Neuroscience. But first I rewrote the Abstract and the Introduction entirely, because I thought that they had been the weak parts of the initial submission. Luckily, the paper went into review. As is our lab policy, we uploaded the preprint of the manuscript to bioRxiv once it went into review (Rupprecht et al., 2022). This was in September 2022.

The reviewers’ requests

The reviewer reports came back ~80 days after submission. Four reviewers! The general tone was positive, appreciative and constructive. The editor had done a good job selecting the reviewers. Besides some more analyses and easy experiments, the reviewers also asked for more “mechanistic insights” and additional (perturbation) experiments to dissect the “molecular” events underlying our observations. The reviewers asked both for pharmacological and optogenetic perturbation experiments. I had anticipated the requests for pharmacology and started to write, in Summer 2022, an animal experiment license to cover those experiments. Fortunately, the license got already approved by beginning of 2023. I started pharmacology experiments with classical drugs affecting the noradrenergic system, e.g., prazosin, DSP-4, etc. Not all of these experiments worked, and all drugs exhibited strong side effects on behavior that confounded the effects we wanted to observe. This way, I learned (again) how messy pharmacology can be when it affects a complex system.

To reduce side-effects, I was planning to use a micropipette to inject e.g. prazosin locally in the imaging FOV under two-photon guidance through a hole drilled into the cover slip. This was an extremely difficult experiment that I did together with Denise Becker in early 2023. It worked for only a single time, and when it exhibited only a small effect, interpretation was difficult. We decided to stop here and use only the previous pharmacology experiments for the paper, with an open discussion of the confounds on animal behavior (now described in the newly added Fig. 8e-f). Altogether, a lot of work with mixed results that were difficult to interpret. Underwhelming!

New collaborations, new experiments

Luckily, via mediation of my colleague Xiaomin Zhang, I realized that there was Sian Duss, a PhD student in the lab of Johannes Bohacek, working on the locus coeruleus. This seemed interesting because the locus coeruleus is one of the key players of arousal, and it would be nice to manipulate this brain region and see what happens to hippocampal astrocytes. It turned out that Sian had done this very same experiment already! She had used fibers to optogenetically stimulate in locus coeruleus and to record from hippocampal astrocytes. And she had observed exactly what we would have predicted from our observations. We could have stopped here, and probably we would have gotten the paper through the revision at Nature Neuroscience.

However, I realized that we could try one more experiment, a bit more challenging, but much more interesting: To optogenetically stimulate locus coeruleus and perform subcellular calcium imaging of astrocytes in hippocampus. And that’s what we did.

First, I wrote an amendment of our animal license to cover these experiments, and after a lot of tedious but efficient Swiss bureaucratic processes, we got it approved in Spring 2023. Sian and I immediately started experiments, rather complicated surgeries with two virus injections, one angled fiber implant and one hippocampal window in transgenic mice. To cut it short, the experiments with Sian were very successful and its outcomes very interesting (check the paper for all the details!).

Final steps towards publication

At this point it was clear to me that the paper would very likely be accepted at Nature Neuroscience. All results of our additional experiments supported the initial findings fully and very cleary. It took me a few more months to analyze all the data, draft a careful rebuttal letter (I did not want to go into a second round of reviews) and re-submit to the journal in August 2023. After two months, we received a message from the journal with “accepted in principle”. Nice!

In the same email, the editors promised to send us a list with additional required modifications from the editorial side. We received those almost two months later, with requests that concerned the title, some important wordings and the length of the manuscript (“please reduce the word count by 45%”). We followed up on that until January and returned the revised manuscript. Then, in March, we received the proofs, treated by a slightly over-motivated copy-editor, and it took me two evenings to fix these changes. In April 2024, exactly 617 days after our submission to Nature Neuroscience, the paper was published online.

Overlap with work of others

Over the duration of the project, I became only gradually aware of similar works, both ongoing or completed. For example, I discovered only during the project work from Christian Henneberger’s lab (King et al., 2020), which inspired the analysis of history-dependent effects of calcium signalling (Fig. 6f). And in Summer of 2023, I talked to his lab members during a conference in Bonn, which helped me refine the Discussion for the revised manuscript.

Specifically related to centripetal propagation, I noticed that such phenomena had already been observed in slices, but rather anecdotally, and hidden in a small supplementary figure (Bindocci et al., 2017). However, in Summer of 2023, a study appeared that showed some of the same effects that we had reported in our preprint in 2022, in somatosensory cortex. I was only later informed that these findings had been obtained independently of our results (Fedotova et al., 2023).

There were also two relevant papers that I had missed entirely before acceptance of our manuscript. First, a study came out in Summer of 2023 (very shortly before we resubmitted our revised manuscript). This very interesting preprint from the Araque lab described somatic integration in cortical astrocytes (Lines et al., 2023). Second, after publication of our manuscript, my co-author Chris Lewis spotted a paper from 2014 that actually described some of the observations that we had thought to have made for the first time, in a small paper with analyses that seemed a bit anecdotal but solid (Kanemaru et al., 2014). I put these two papers on my list “I should have cited them and will definitely do so at the next opportunity!”

Future directions and follow-ups

One of the greatest parts of this project were the experiments done in 2023 with Sian Duss, an extremely skilled experimenter and great scientist. It turned out that she was eager to continue the collaboration to better understand the effects of locus coeruleus on hippocampus (and so was I). While doing experiments with her, so many interesting observations popped up that I find it hard to restrain my scientific curiosity and not dive into all these different observations, each of them probably worth a few years of intense scrutiny!

I’m very much looking forward to seeing what the future will bring; but I’m sure that there will always be at least a small (or large) part of my scientific work focusing on astrocytes.

.

.

References

Aronov, D., Nevers, R., Tank, D.W., 2017. Mapping of a non-spatial dimension by the hippocampal/entorhinal circuit. Nature 543, 719–722. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21692

Bindocci, E., Savtchouk, I., Liaudet, N., Becker, D., Carriero, G., Volterra, A., 2017. Three-dimensional Ca2+ imaging advances understanding of astrocyte biology. Science 356, eaai8185. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aai8185

Ding, F., O’Donnell, J., Thrane, A.S., Zeppenfeld, D., Kang, H., Xie, L., Wang, F., Nedergaard, M., 2013. α1-Adrenergic receptors mediate coordinated Ca2+ signaling of cortical astrocytes in awake, behaving mice. Cell Calcium 54, 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceca.2013.09.001

Doron, A., Rubin, A., Benmelech-Chovav, A., Benaim, N., Carmi, T., Refaeli, R., Novick, N., Kreisel, T., Ziv, Y., Goshen, I., 2022. Hippocampal astrocytes encode reward location. Nature 609, 772–778. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05146-6

Eichenbaum, H., 2014. Time cells in the hippocampus: a new dimension for mapping memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 732–744. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3827

Fedotova, A., Brazhe, A., Doronin, M., Toptunov, D., Pryazhnikov, E., Khiroug, L., Verkhratsky, A., Semyanov, A., 2023. Dissociation Between Neuronal and Astrocytic Calcium Activity in Response to Locomotion in Mice. Function 4, zqad019. https://doi.org/10.1093/function/zqad019

Kanemaru, K., Sekiya, H., Xu, M., Satoh, K., Kitajima, N., Yoshida, K., Okubo, Y., Sasaki, T., Moritoh, S., Hasuwa, H., Mimura, M., Horikawa, K., Matsui, K., Nagai, T., Iino, M., Tanaka, K.F., 2014. In Vivo Visualization of Subtle, Transient, and Local Activity of Astrocytes Using an Ultrasensitive Ca2+ Indicator. Cell Rep. 8, 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.056

King, C.M., Bohmbach, K., Minge, D., Delekate, A., Zheng, K., Reynolds, J., Rakers, C., Zeug, A., Petzold, G.C., Rusakov, D.A., Henneberger, C., 2020. Local Resting Ca2+ Controls the Scale of Astroglial Ca2+ Signals. Cell Rep. 30, 3466-3477.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.043

Larkum, M., 2013. A cellular mechanism for cortical associations: an organizing principle for the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci. 36, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.006

Lines, J., Baraibar, A., Nanclares, C., Martín, E.D., Aguilar, J., Kofuji, P., Navarrete, M., Araque, A., 2023. A spatial threshold for astrocyte calcium surge. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.18.549563

Nimmerjahn, A., Mukamel, E.A., Schnitzer, M.J., 2009. Motor Behavior Activates Bergmann Glial Networks. Neuron 62, 400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.019

Paukert, M., Agarwal, A., Cha, J., Doze, V.A., Kang, J.U., Bergles, D.E., 2014. Norepinephrine controls astroglial responsiveness to local circuit activity. Neuron 82, 1263–1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.038

Rupprecht, P., Carta, S., Hoffmann, A., Echizen, M., Blot, A., Kwan, A.C., Dan, Y., Hofer, S.B., Kitamura, K., Helmchen, F., Friedrich, R.W., 2021. A database and deep learning toolbox for noise-optimized, generalized spike inference from calcium imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1324–1337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00895-5

Rupprecht, P., Duss, S.N., Becker, D., Lewis, C.M., Bohacek, J., Helmchen, F., 2024. Centripetal integration of past events in hippocampal astrocytes regulated by locus coeruleus. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 927–939. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01612-8

Rupprecht, P., Lewis, C.M., Helmchen, F., 2022. Centripetal integration of past events by hippocampal astrocytes. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.504030

Schmidt, E., Oheim, M., 2020. Infrared Excitation Induces Heating and Calcium Microdomain Hyperactivity in Cortical Astrocytes. Biophys. J. 119, 2153–2165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.10.027

Stobart, J.L., Ferrari, K.D., Barrett, M.J.P., Glück, C., Stobart, M.J., Zuend, M., Weber, B., 2018. Cortical Circuit Activity Evokes Rapid Astrocyte Calcium Signals on a Similar Timescale to Neurons. Neuron 98, 726-735.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.050

I’ve imagined the difficulties in doing research and getting it published, but it was good to read an actual account of it. It’s really hard work, I can’t see, with a lot of twists and turns to get results.

What actually are these astrocytes doing in hippocampus during centripetal propagation? Are they actually participating directly in hippocampal functions like memory or location processing?

Hi James,

Thanks for your comment! I agree, there is a lot of things going on that is hidden from the reader of the final publication. Glad it was interesting for you!

For your question: Location processing is something that is probably done on a fast timescale (< 1-2 seconds), I guess that astrocytes with their slow activity is unlikely to be involved in a similar manner as pyramidal place cells of the hippocampus. I could very well imagine that memory is one of the functions mediated by astrocytes that are activated upon centripetal integration. These are ideas that are around in the astrocyte community since long. Here, for example, is a very recent study on astrocytic activation and neuronal plasticity in hippocampus: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.21.595135v2 Given works such as this one, it seem quite intuitive to imagine that conditional centripetal propagation, which we observed, plays a role to gate neuronal plasticity (and therefore memory).

Hi Dr. Rupprecht, thank you for writing such a detailed blog. I read your paper in a biorxiv version two years ago, and I had no idea how much effort and struggles you’ve been through. Thank you for inspiring me.

In regard to astrocytes, I have some naive questions and immature thoughts. How significant a role do astrocytes play in modulating brain states? I ask this because, while I’d love to consider astrocytes as the driving force/motivation behind different brain state, some evidence often suggests that they are more passive listener to either above-threshold or under-threshold signals from neurons. For instance, many studies focus on correlation instead of causality analysis when it comes to astrocytes. Additionally, astrocytes seem to have a high correlation with locomotion and vascular tone. Therefore, I’m a bit concerned that astrocytes might be more likely listeners than active modulators.

I’d love to hear your opinions.

Hi,

Thanks for your comment!

To my understanding, the question to which extent astrocytes modulate brain states or are only passive listeners to neurons that reflect brain state is still unresolved. In our study, we clearly observed how astrocytes were modulated by brain state (and specifically by locus coeruleus in the brain stem), but we did not find evidence for a role of astrocytes to modulate brain state or neurons. But absence of evidence does not mean evidence for the absence of any effect …

There are, however, a couple of lines of evidence that astrocytes do have direct and specific effects on neurons (or blood vessels). In a recent blog post (https://gcamp6f.com/2024/07/08/four-recent-interesting-papers-on-astrocyte-neuroscience/), I mentioned two of those: (1) Lind and Volterra showed that under certain conditions astrocytic endfeet can control the dilation of blood vessels. (2) Lefton et al. showed that astrocytes can under certain conditions influence presynaptic activity. Both effects are not only correlational. Still, it remains difficult to properly evaluate the importance of astrocytes as a potentially active as opposed to passive component of the brain. I have the impression that people working with astrocytes tend to overstate the importance of astrocytes, while people not working with astrocytes tend to underestimate it – it’s difficult to get to a realistic assessment ;-)

There are actually many studies claiming a causal role of astrocytes for a specific behavior. For example, researchers perturb astrocytic function using DREADDs or other tools and then see e.g. a memory deficiency. I would try to interpret such studies with a lot of care. Astrocytes are a part of the neural system, and if the neural system is perturbed, also the behavior is affected; but this does not mean that the astrocytes have specific effects on behavior. In this case, astrocytes could very well be a necessary enabling factor for proper memory function (similar to drinking water is necessary for humans to be able to run), but not the principal mechanism of how memory is formed.

In any case, it is clear that astrocytes listen to many things going on in the brain. But are they really “passive” listeners only, as your comment suggests? To me it seems likely that astrocytes do indeed first of all listen to the ongoing activity in the brain, but it would be a waste of resources to make them not do anything with the information they listen to! One reason why we don’t yet understand their actions is that these actions might be manifold (mediatted by various signaling molecules), slower (since astrocytes react more slowly than neurons) and not so obvious to observe. The action of neuron is very obvious (the action potential), which makes it easy to study with electrophysiology. The action of astrocytes might be more molecular (release of adenosine, lactate, D-serine, etc.) and more difficult to monitor with our current set of methods. Currently, there are many different opinions among astrocyte experts about the most important molecule that astrocytes use to act upon the brain. I believe that, with improving sensor technologies for such molecules, we will be able to understand more about the action of astrocytes during the next decades. Currently, our understanding is quite limited – so, much research still needs to be done on that!

You might also be interested in reading this recent interview with Andrea Volterra: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-024-01721-4

He’s one of the pioneers of the idea that astrocytes are active and not only passive components of the brain (therefore a quite biased view). It is interesting to read why he thinks so and how he judges the early experiments and ideas in hindsight.

Hi Dr. Rupprecht,

Thank you so much for your detailed reply and paper recommendations! I read them along with the interview, and I completely agree with the idea from the interview that we should focus on our data without oversimplifying or overinterpreting it. However, Dr. Volterra didn’t provide specific suggestions on the top questions we can possibly answer in astrocyte studies today. I was wondering if you could share some of your ideas? I apologize if this question is a bit too broad, but any of your insights would be beneficial to us.

Best wishes,

Sijia

Hi Sijia,

The questions that I personally find most intriguing about astrocytes:

(1) How do astrocytes react differently towards different signaling molecules? For example, where are the different receptor types for glutamate, GABA, noradrenalin, acetylcholine located on the astrocytic morphology, and how does the response of astrocytes differ depending on the signaling molecule?

(2) What molecules do astrocytes use to act upon their environment? Gliotransmission is the key word brought up in Andrea Volterra’s interview, but other molecules seem to be important as well (as mentioned in my earlier reply).

There is probably no simple answer to these very basic questions, because there is a diversity of astrocytes, and different astrocytes (also within the same brain region) might respond differently.

The key challenge to address both questions could be to develop the appropriate methods. Probably this means developping fluorescent sensors that reliably reflect the local intra- and extracellular concentration of these signaling molecules. Currently, we have good sensors for calcium, for voltage, and maybe for glutamate. But even sensors for noradrenaline and other molecules are at the moment probably not as sensitive as needed for these kind of approaches.

As of now, we don’t have a good overview of both these topics. To get an understanding of astrocytes, we need to aim for this full picture, not just pieces and fragments and single signaling pathways – we need to be able to compare those pathways.

Thank you so much!