One of the most amazing methods in modern neuroscience is dense volumetric electron microscopy of the brain. I have mentioned some openly accessible datasets before (see my previous blog post), but many additional datasets have been released since then – most prominently from drosophila, but also from zebra finch, zebrafish, mouse, and even the human brain.

My own research in the lab is primarily focused on the hippocampus, so I am always specifically curious about hippocampal datasets. There’s a relatively old one by Bloss et al. (2018) obtained from mouse hippocampus. However, when I saw a new hippocampal dataset published earlier this year, I was quite intrigued. This new dataset, described by Corteze et al. (2025) in a preprint from Helene Schmidt‘s lab in Frankfurt, was acquired in “coronal” slices, resembling how the rodent hippocampus (or at least dorsal CA1) is often visualized in standard histology. This acquisition modality clearly reveals the hippocampal layers, making it easy to navigate, even for non-experts not familiar with electron microscopy data. You can browse the dataset just by clicking for example on this link: https://wklink.org/7023

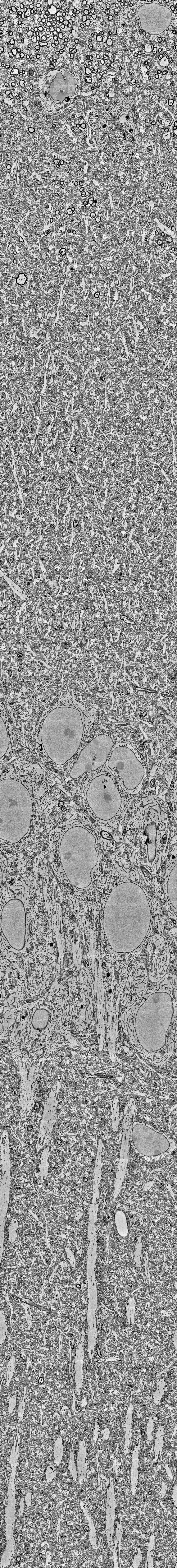

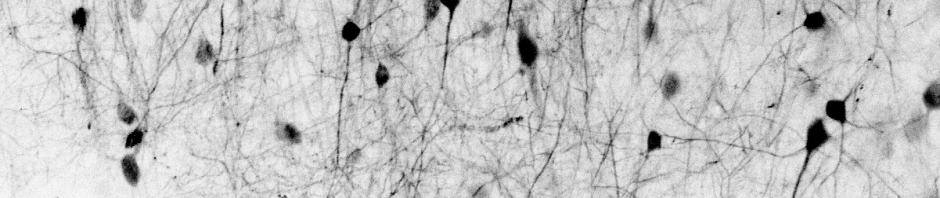

The layering of the hippocampus that can be seen in these images is really beautiful (see picture below). At the top, you see the myelinated axons of the corpus callosum, then the small dendrites of the stratum oriens, then the dense layer of pyramidal neurons’ cell bodies. Going further, you can clearly trace the huge apical dendrites of pyramidal cells – if you ever wondered why apical dendrites are visible even under regular light microscopy while smaller dendrites are not, here is your answer. What a beautiful layering; and how difficult to visualize without extensive scrolling!

Unfortunately, all the fine details like small dendrites, axon myelin sheaths or mitochondria are barely visible when you zoom out on a normal screen; and the overall architecture of the hippocampus, in return, becomes hard to see when you zoom in. To visualize both scales, I decided to print out the hippocampal “column” and use it to decorate a small section of my office wall.

Downloading the data takes a bit of coding. A screen capture doesn’t work because the data browser adapts the resolution of the currently rendered view (using a multi-resolution pyramid data format). So, I wrote a small script (on GitHub) which downloads one single coronal imaging plane from the server to my own hard disk. (Downloading the whole dataset would be prohibitive due to its size.) Then I selected the hippocampal “column” that I wanted to have on my walls.

Next, I printed the hippocampal EM image as a poster – actually, it was three A0 posters to span the full height of my office, which is over 3 meters. To stabilize the posters, I glued them onto thin wooden panels bought from a local hardware store.

Next, I measured the boundaries of the surrounding walls and doors to make the panels fit into the shapes of walls, door, and ceiling. Stefan Giger and Martin Wieckhorst, who have access to a bench saw at the institute, kindly cut the panels to make them fit into the space. I covered the connecting edges where two panels met with black insulation tape, and used short nails to attach the panels to the walls.

For the next iteration, I would probably use a more expensive glossy print. However, overall I’m quite happy with the result. Here’s a glimpse of how the corpus callosum with its myelinated axons nicely fits the ceiling:

Can we get a T-shirt (not the entire thing, of course)?

Maybe not the best T-shirt material since it becomes less impressive if you only see a 10 x 10 um^2 excerpt. But maybe one could give it a try – I have never seen EM data used for T-shirt design so far.

I like to wear odd t-shirts. But I think a section of the brain, especially if color coded, in a wrap-around style might look like abstract art (of which I am also a fan).