How does the brain work, and how can we understand it? To approach this big question from a broad perspective, I want to report on some ideas about the brain that marked me most over the past twelve months and that, on the other hand, do not overlap too much with my own research focus. Enjoy the read! And check out previous year-end write-ups: 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024.

For this year’s wrap-up, I reflect on what it would really mean to achieve experimental goals that currently seem out of reach.

This is part II, with part I online already and part III following in a couple of days.

II. Recording the inputs and the output of a single neuron in real time in vivo

The idea:

Suppose all neurons are, in some sense, similar. Then, understanding the principles governing a single neuron’s behavior might suffice to understand the brain: you only need to assemble many such neurons into a circuit, and intelligent behavior will emerge. This idea resembles what we see in simple organisms, or even amoebae, where individual agents follow simple rules but collectively produce complex, emergent behavior.

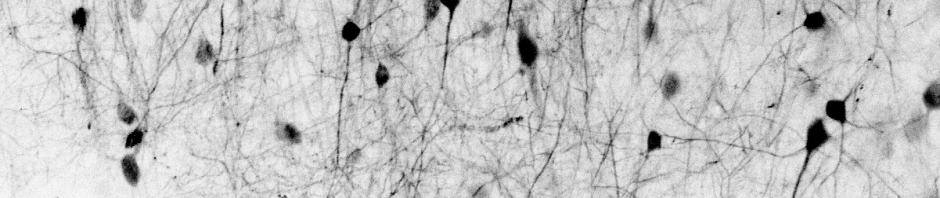

One way to understand a single neuron is to record all its synaptic inputs while simultaneously measuring when it generates action potentials (its output). In principle, we know the components responsible for this “integration”: voltage propagation from synaptic spines through dendrites to the soma; various voltage-dependent and voltage-independent ion channels for potassium, sodium, and calcium; and other molecular details that we may ignore for now. While synaptic integration was studied extensively in slices in the late 1990s and early 2000s (and still is nowadays to a lesser extent), it remains unclear how all of this plays out in the living brain. Wouldn’t it be fascinating to record all inputs and the output of a neuron simultaneously?

Why it won’t work:

To achieve subcellular resolution for a single neuron in a living animal, that neuron must first be fluorescently labeled. Ideally, only that neuron would be targeted to avoid background fluorescence. This may be achieved using specialized viral strategies for sparse labeling (Jefferis and Livet, 2012), or by targeted single-cell electroporation (Gonzalez et al., 2025b). The next challenge is to simultaneously observe all of the neuron’s dendrites and spines and their activity. A typical layer 5 cortical neuron spans almost the entire cortical depth; in mice, its dendrites extend over more than 600 micrometers.

The only method that allows imaging at such depths in vivo with acceptable speed is two-photon microscopy (Helmchen and Denk, 2005). However, even two-photon microscopy is relatively slow, making it impossible to scan an entire dendritic tree at sufficient speed. Scanning speed is fundamentally limited by fluorescence lifetime (approx. 3 ns), preventing us from reaching the speeds required to sample a complete dendritic arbor (dendritic length of a single pyramidal cell: approx. 10’000 µm). Dedicated microscopes based on AOD scanners have been built for this purpose (Akemann et al., 2022; Grewe et al., 2010; Katona et al., 2012; Nadella et al., 2016), but none of them can scan 10 mm of dendritic length distributed across >600 micrometers at high speed. But not only the scan speed is limiting, but also the fluorescence yield: even if we managed to quickly scan across the entire dendrite and excite each point of the dendrite, we may not get a lot of fluorescence from it due to the low number of fluorophors. But, even though I play the devil’s advocate here, I have to admit that we’re not completely out of sight of the goal. And there are new scanning technologies (Demas et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2025) that are not fully applicable for this purpose but make us aware that for neuroscience and microscopy the impossible might actually be possible in the future. And even now, we may be able to scan a substantial portion of a neuron’s dendritic tree (maybe 10% of it) at a reasonable speed.

But let’s talk about the fluorophores and what they measure. The most commonly used fluorophores for this task are calcium indicators. They are relatively bright and slow, which makes them ideal to record across an entire neuron, where it takes some time to scan the entire dendritic tree. However, they primarily reflect the neuronal output (the action potential in the soma and axon, and the backpropagating action potential in the dendrites). Inputs in dendrites are often not seen at all, or overshadowed by the backpropagating action potential (Francioni et al., 2019). In spines, there are studies which show that inputs can be recorded without contamination by backpropagating action potentials (Iacaruso et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2016), but these analyses still come with a lot of uncertainty and have been questioned by future experiments and analyses (Kerlin et al., 2019). Also, inhibitory synapses don’t come with spines and would therefore be missed entirely. New classes of sensors could fix this problem, detecting either glutamate (or GABA for inhibitory synapses) (Aggarwal et al., 2025; Kolb et al., 2025) or the membrane potential (voltage indicators) (Hao et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022). These sensors are, however, faster, making it necessary to record at a repetition rate of almost 1000 Hz (or a bit lower for subthreshold events). With current sensors and two-photon recording modalities, it seems difficult to imagine performing such recordings for a entire dendritic tree, at high speed, high signal-to-noise, and at high spatial resolution. (Gonzalez et al., 2025a) published a study which comes closest to this ideal experiment and is definitely worth a read.

What we would learn:

The primary result would be a complete description of how a neuron processes synaptic information. How do synapses on the apical dendrite, hundreds of micrometers from the soma, influence the decision to fire an action potential? How linear or nonlinear is signal integration, really? These are straightforward, and maybe somewhat academic, questions that have remained unresolved for a long time (Stuart et al., 2016). But the implications of such an experimental dataset would go much further. By observing synaptic inputs over long periods, we could precisely determine how similar neighboring inputs are. In addition, and more importantly, we would see how activity patterns that do or do not coincide with somatic action potentials are strengthened or weakened over time. For example, if a synapse is repeatedly active but never supported by neighboring or spatially distant synapses, it should eventually weaken and be eliminated morphologically. But according to which exact rules does this remodeling occur? How many futile activations are required before weakening begins? Does weakening affect only that synapse, or neighboring ones as well? Such questions about coordinated plasticity of clustered synapses are already addressed at a smaller scale (Kastellakis and Poirazi, 2019; Larkum and Nevian, 2008; Ujfalussy and Makara, 2020), but they are hampered by incomplete pictures and contaminated readouts of inputs vs. outputs.

Overall, these research topics may sound like small details for scientists not working in this field, but it is precisely such details that define the generative rules governing neuronal function. Therefore, the major advance of this experiment would be the systematic exploration of many such rules – details that are currently known only sparsely or from isolated slice experiments. The result of this experiment would be a lexicon of rules describing how current neuronal activity shapes future input strength. In essence, these are the rules for the plasticity and learning of individual neurons. With these plasticity rules, we could understand the principles individual neurons follow as actors within a collective that performs intelligent information processing and storage.

Going conceptually slightly beyond that, the dataset would allow us to address questions that are currently out of reach. One such idea, which I have discussed previously on this blog, is that neuronal action potentials should be interpreted as actions of cells (with cells considered as agents); in this scheme, subsequent synaptic inputs would represent the feedback/reaction received, as described also elsewhere in more detail with the concept of individual neurons as control units(Moore et al., 2024). This perspective places the single neuron back at the center, framing the closed loop of action and reaction from the neuron’s point of view. An experiment that simultaneously records inputs and output of a single cell would make such ideas, which are currently untestable, empirically accessible.

References

Aggarwal, A., Negrean, A., Chen, Y., Iyer, R., Reep, D., Liu, A., Palutla, A., Xie, M.E., MacLennan, B.J., Hagihara, K.M., Kinsey, L.W., Sun, J.L., Yao, P., Zheng, J., Tsang, A., Tsegaye, G., Zhang, Y., Patel, R.H., Arthur, B.J., Hiblot, J., Leippe, P., Tarnawski, M., Marvin, J.S., Vevea, J.D., Turaga, S.C., Tebo, A.G., Carandini, M., Rossi, L.F., Kleinfeld, D., Konnerth, A., Svoboda, K., Turner, G.C., Hasseman, J.P., Podgorski, K., 2025. Glutamate indicators with increased sensitivity and tailored deactivation rates. Nat Methods. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02965-z

Akemann, W., Wolf, S., Villette, V., Mathieu, B., Tangara, A., Fodor, J., Ventalon, C., Léger, J.-F., Dieudonné, S., Bourdieu, L., 2022. Fast optical recording of neuronal activity by three-dimensional custom-access serial holography. Nat Methods 19, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01329-7

Demas, J., Manley, J., Tejera, F., Barber, K., Kim, H., Traub, F.M., Chen, B., Vaziri, A., 2021. High-speed, cortex-wide volumetric recording of neuroactivity at cellular resolution using light beads microscopy. Nat Methods 18, 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01239-8

Francioni, V., Padamsey, Z., Rochefort, N.L., 2019. High and asymmetric somato-dendritic coupling of V1 layer 5 neurons independent of visual stimulation and locomotion. eLife 8, e49145. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49145

Gonzalez, K.C., Negrean, A., Liao, Z., Terada, S., Zhang, G., Lee, S., Ócsai, K., Rózsa, B.J., Lin, M.Z., Polleux, F., Losonczy, A., 2025a. Synaptic basis of feature selectivity in hippocampal neurons. Nature 637, 1152–1160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08325-9

Gonzalez, K.C., Noguchi, A., Zakka, G., Yong, H.C., Terada, S., Szoboszlay, M., O’Hare, J., Negrean, A., Geiller, T., Polleux, F., Losonczy, A., 2025b. Visually guided in vivo single-cell electroporation for monitoring and manipulating mammalian hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc 20, 1468–1484. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01099-4

Grewe, B.F., Langer, D., Kasper, H., Kampa, B.M., Helmchen, F., 2010. High-speed in vivo calcium imaging reveals neuronal network activity with near-millisecond precision. Nat Methods 7, 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1453

Hao, Y.A., Lee, S., Roth, R.H., Natale, S., Gomez, L., Taxidis, J., O’Neill, P.S., Villette, V., Bradley, J., Wang, Z., Jiang, D., Zhang, G., Sheng, M., Lu, D., Boyden, E., Delvendahl, I., Golshani, P., Wernig, M., Feldman, D.E., Ji, N., Ding, J., Südhof, T.C., Clandinin, T.R., Lin, M.Z., 2024. A fast and responsive voltage indicator with enhanced sensitivity for unitary synaptic events. Neuron 112, 3680-3696.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2024.08.019

Helmchen, F., Denk, W., 2005. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat Methods 2, 932–940. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth818

Iacaruso, M.F., Gasler, I.T., Hofer, S.B., 2017. Synaptic organization of visual space in primary visual cortex. Nature 547, 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23019

Jefferis, G.S., Livet, J., 2012. Sparse and combinatorial neuron labelling. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 22, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.010

Kastellakis, G., Poirazi, P., 2019. Synaptic Clustering and Memory Formation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12, 300. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00300

Katona, G., Szalay, G., Maák, P., Kaszás, A., Veress, M., Hillier, D., Chiovini, B., Vizi, E.S., Roska, B., Rózsa, B., 2012. Fast two-photon in vivo imaging with three-dimensional random-access scanning in large tissue volumes. Nat Methods 9, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1851

Kerlin, A., Mohar, B., Flickinger, D., MacLennan, B.J., Dean, M.B., Davis, C., Spruston, N., Svoboda, K., 2019. Functional clustering of dendritic activity during decision-making. eLife 8, e46966. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.46966

Kolb, I., Hasseman, J.P., Matsumoto, A., Jensen, T.P., Kopach, O., Arthur, B.J., Zhang, Y., Tsang, A., Reep, D., Tsegaye, G., Zheng, J., Patel, R.H., Looger, L.L., Marvin, J.S., Korff, W.L., Rusakov, D.A., Yonehara, K., GENIE Project Team, Turner, G.C., 2025. iGABASnFR2: Improved genetically encoded protein sensors of GABA. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.108319.1

Larkum, M.E., Nevian, T., 2008. Synaptic clustering by dendritic signalling mechanisms. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 18, 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.013

Liu, Z., Lu, X., Villette, V., Gou, Y., Colbert, K.L., Lai, S., Guan, S., Land, M.A., Lee, J., Assefa, T., Zollinger, D.R., Korympidou, M.M., Vlasits, A.L., Pang, M.M., Su, S., Cai, C., Froudarakis, E., Zhou, N., Patel, S.S., Smith, C.L., Ayon, A., Bizouard, P., Bradley, J., Franke, K., Clandinin, T.R., Giovannucci, A., Tolias, A.S., Reimer, J., Dieudonné, S., St-Pierre, F., 2022. Sustained deep-tissue voltage recording using a fast indicator evolved for two-photon microscopy. Cell 185, 3408-3425.e29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.07.013

Moore, J.J., Genkin, A., Tournoy, M., Pughe-Sanford, J.L., De Ruyter Van Steveninck, R.R., Chklovskii, D.B., 2024. The neuron as a direct data-driven controller. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2311893121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2311893121

Nadella, K.M.N.S., Roš, H., Baragli, C., Griffiths, V.A., Konstantinou, G., Koimtzis, T., Evans, G.J., Kirkby, P.A., Silver, R.A., 2016. Random-access scanning microscopy for 3D imaging in awake behaving animals. Nat Methods 13, 1001–1004. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4033

Stuart, G., Spruston, N., Häusser, M. (Eds.), 2016. Dendrites. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198745273.001.0001

Ujfalussy, B.B., Makara, J.K., 2020. Impact of functional synapse clusters on neuronal response selectivity. Nat Commun 11, 1413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15147-6

Wilson, D.E., Whitney, D.E., Scholl, B., Fitzpatrick, D., 2016. Orientation selectivity and the functional clustering of synaptic inputs in primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci 19, 1003–1009. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4323

Zhong, J., Natan, R.G., Zhang, Q., Wong, J.S.J., Miehl, C., Bose, K., Lu, X., St-Pierre, F., Guo, S., Doiron, B., Tsia, K.K., Ji, N., 2025. FACED 2.0 enables large-scale voltage and calcium imaging in vivo. Nat Methods. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02925-7

Pingback: Annual report of my intuition about the brain (2025, part I) | A blog about neurophysiology

Pingback: Annual report of my intuition about the brain (2025, part III) | A blog about neurophysiology

I’m not an expert in this field, but I’m very curious about these latest scientific developments from an AI perspective. In your report, you discuss the technical challenges of imaging a full Layer 5 pyramidal neuron in vivo, especially due to its extensive dendritic arbor and depth.

I was wondering if it might make sense to attempt similar experiments with neurons in Layers 2/3, which have more compact dendritic trees and are closer to the surface. Could current imaging techniques, such as two-photon microscopy combined with fast glutamate sensors like iGluSnFR4f, be better suited for these smaller, more superficial neurons?

Thank you very much for your time and insights.

That’s a good point! It may indeed make sense to first focus on smaller neurons, such as Layer 2/3 pyramidal cells, or hippocampal pyramidal cells. The reason why I brought up L5 neurons is that many theories of cortical learning and the core model circuit of the cortex focus on L5 neurons.

To your question: Two-photon microscopy with iGluSnFR sensors of a full L2/3 neuron might be still out of reach. I’m not aware of any study performing imaging of glutamate sensors in more than a handful of dendritic segments in vivo. Scaling this up to a full dendritic tree might be still far away. However, I have to guess myself since I’ve used glutamate sensors only for a preliminary test experiment some time ago.

It may be that ultra-sparse labeling (expression only in a single L2/3 neuron) together with one-photon instead of two-photon imaging could be the way to get more photons and to cover a larger fraction of the dendritic tree – the next 10 years will show!