How does the brain work, and how can we understand it? To approach this big question from a broad perspective, I want to report on some ideas about the brain that marked me most over the past twelve months and that, on the other hand, do not overlap too much with my own research focus. Enjoy the read! And check out previous year-end write-ups: 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024.

During a talk in Basel in 1980, Sydney Brenner stated that “so much progress depends on the interplay of techniques, discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order of decreasing importance” (Brenner, 2002). This statement got converted into the famous quote: “Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries, and new ideas, probably in that order”. What is missing from the famous quote is the word interplay. This omission highlights what scientific research truly needs, and something that proponents of technology development often forget to mention: technology needs to interact with scientific ideas and discoveries in order to become powerful.

Sometimes I get the impression that neurotechnology takes on a life of its own and is developed for its own sake. The fact that the ultimate goal of a specific technology is unattainable seem to discourage interaction with ideas, because those ideas are not within reach, and investments into technology alone seems therefore more reasonable. That is why I want to try today to think through what it would actually mean if we could indeed achieve three different seemingly unachievable experimental goals.

Here comes part I, with parts II and III following in a couple of days.

I. Reconstructing memories and mind from the connectome of a human brain

The idea:

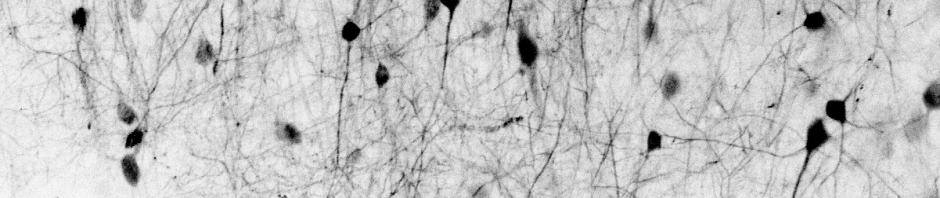

Synaptic connections between neurons can be observed anatomically as long as the spatial precision is high enough, which can be achieved with electron microscopy that can achieve a resolution of a few nanometers. Other methods, such as expansion microscopy (Tavakoli et al., 2025) or X-ray tomography (Bosch et al., 2025), may provide similar resolution in the future, but the basic assumption does not change: the brain must already be dead (preferably not for too long). If it were possible to image an entire human brain with electron microscopy and detect all synapses and their strengths, we would obtain the (synaptic) connectome: all connections between all neurons, including their weights. Like an artificial neural network, this biology-derived network could then be run in a simulation, reconstructing the knowledge and experiential world of the dead brain. There is even a not-so-small community that hopes that such a method could grant them some form of life after death and, therefore, immortality.

Why it won’t work:

In principle, the method itself works very well. In 2025, connectomics was even named “Method of the Year” by Nature Methods (Marx, 2025). Over the past years, connectomics has provided fascinating insights into brain organization, particularly in simpler animals, most notably the fruit fly Drosophila. For the fruit fly, the connectome was approached five years ago (the “hemibrain” dataset) (Scheffer et al., 2020) and nearly completely reconstructed more recently (Dorkenwald et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2024; Matsliah et al., 2024; Schlegel et al., 2024). Since individual neurons are arranged almost identically from fly to fly, this catalog has become extremely useful for the entire fruit fly community.

So why shouldn’t this also work for a mammalian or human brain? For several reasons. First, the human brain is simply too large. Even imaging small brains or brain fragments is currently an enormous challenge. Producing a single high-quality, high-resolution 2D image of brain tissue is not particularly difficult. Maintaining that same quality across thousands, millions, or billions of images is. If we say that one image is 4096×4096 pixels, and we wanted to image at 10 nm resolution in x and y (the fruit fly connectomes use even higher resolutions) and in 20 nm slices in z, we would need to record roughly 1020 imaging voxels for a 1-2 liter volume of human brain tissue, or 6 1012 (or 6 trillion) images. Which is a lot of images that need to be acquired without mistakes! If even one small brain region hidden in a corner is not well captured, the entire idea of a complete connectome is called into question. Microscopes can fail due to power outages; cutting blades may drag a dust particle across the sample and scratch entire image series; heavy metals used for contrast may not penetrate certain brain regions well enough to reveal synapses. Any such high-precision methods are inherently fragile and error-prone, making them less scalable. When imaging a fruit fly brain, this is manageable – you can simply try again with another brain of another fly until the sample quality is sufficient and your software does not produce a critical crash. But if you want to reconstruct the connectome of a specific human, you get only one attempt.

Second, there is the issue of data analysis. Manually reconstructing a single human neuron takes several days, or, according to more optimistic views (which I do not share), a few hours. The human brain contains roughly 100 billion neurons. Who is supposed to do this work? AI, of course. There are already impressive methods for automated segmentation of neurons and detection of synapses. However, in all cases, manual validation is still required to correct false mergers and reassemble neurons that have been split during segmentation. Researchers have tried to automate this process (Celii et al., 2025; Schmidt et al., 2024), but in practice these steps are still mostly performed by humans. Could AI fully automate this time-critical step? Probably yes. Will it happen in the near future? At present, I see little concrete evidence, only preliminary prototypes and promises.

Third, an open question is how much we would actually learn from the connectome. How much information can be inferred from the anatomical appearance of a synapse? Can we tell which neurotransmitter it uses, or whether the synapse adapts or facilitates to incoming input? How can we reconstruct dynamic activity patterns from static synapses? Can we understand how a synapse on a spine interacts in terms of electrophysiologcally with the dendrite and soma based solely on an electron micrograph? How can we take into account molecular details such as voltage-gated ion channels and their distribution? All of these aspects are under active investigation, but they are far from being resolved. And it remains unclear (with unclear, I mean as unclear as in the halting problem) when they will be understood well enough so we can judge whether a purely anatomical connectome is sufficient to reconstruct memories and the inner life of a brain, be it human or not.

Based on these considerations, I still believe that connectomics is one of several essential methods in basic neuroscience, and certainly one of the most promising. But even if a connectomic anatomical reconstruction worked perfectly, it would not suddenly mean that we can wake up the mind from a dead brain with its dynamics.

What we would learn:

Suppose we could reconstruct all neurons in a human brain and detect all synapses, assigning each a weight that reflects its true functional strength (even though it is still unclear whether this is fully possible). We could systematically revisit and test many existing findings in neuroscience. For example, global connectivity in the human brain is often measured using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which relies on anisotropic diffusion of water molecules along fiber bundles. It would be both exciting and important to validate and refine this method using a connectome, improving accuracy by several orders of magnitude.

Even more importantly, a connectome would revolutionize research fields that focus on specific brain regions. For example, there are relatively large research communities for each of the major cortical and non-cortical brain areas such as the basolateral amygdala (processing of emotion and fear), the locus coeruleus (stress and arousal), or the hypothalamus (homeostasis and endocrine control). A recurring question is: where does this region actually receive its inputs from? For that, current neuroscience heavily relies on retrograde (virus) tracing, which labels neurons projecting to a given region. These methods are powerful but not fully reliable, as injections are difficult to restrict spatially, and viruses often have unexplained biases for or against certain neurons’ axons. A connectome would replace all such experiments in one stroke.

But it would go much further. We could examine not only the inputs to a region, but the inputs to those inputs – mapping the full receptive field of a region or even specific cell types. Conversely, we could finally understand the impact of a region or neuron: where do its axons project, and where do the axons of its downstream targets project? Analogous to a receptive area, we could map an impact field in a clear and systematic way.

With a connectome, many theories about the organization of brain regions could be decisively confirmed or discarded. With today’s relatively small datasets from animal experiments, this is already partially possible, though with major limitations, as shown, for example, in work from Moritz Helmstaedter’s lab, testing ideas such as predictive processing or the standard model of the cortical column (Sievers et al., 2024). For open questions like the importance of recurrent connectivity in the hippocampus or olfactory cortex, functional characterization of recurrence currently requires enormous effort with weak statistical power (Guzman et al., 2016; Layous et al., 2025). Right now, we have no good intuition about the prevalance of recurrent connections throughout brain areas and what kind of anatomical recurrences (single-synaptic loops, loops between thalamus and cortex, loops between specific cortical layers). Even a single connectome could clarify these issues immediately.

As with the fruit fly brain, such a dataset would be publicly accessible and would therefore constitute a reference for everyone, enabling any researcher or even interested laypeople to contribute not only ideas but also corrections, and thus making a big contribution to open science.

Overall, it is difficult to overstate the potential impact of a complete connectome. Yet, some scientists manage to do exactly that by claiming it would allow reconstruction of a person’s full memories. That remains far away and just as unrealistic as the promises made by the Blue Brain Project in the early 2000s. It is harder – but necessary – to explain to non-experts why the connectome would not deliver this result, and still be an absolute game changer.

References

Bosch, C., Aidukas, T., Holler, M., Pacureanu, A., Müller, E., Peddie, C.J., Zhang, Y., Cook, P., Collinson, L., Bunk, O., Menzel, A., Guizar-Sicairos, M., Aeppli, G., Diaz, A., Wanner, A.A., Schaefer, A.T., 2025. Nondestructive X-ray tomography of brain tissue ultrastructure. Nat Methods 22, 2631–2638. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02891-0

Brenner, S., 2002. Life sentences: Detective Rummage investigates. Genome Biology 3.

Celii, B., et al., 2025. NEURD offers automated proofreading and feature extraction for connectomics. Nature 640, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08660-5

Dorkenwald, S., et al., 2024. Neuronal wiring diagram of an adult brain. Nature 634, 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07558-y

Guzman, S.J., Schlögl, A., Frotscher, M., Jonas, P., 2016. Synaptic mechanisms of pattern completion in the hippocampal CA3 network. Science 353, 1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf1836

Layous, R., Tamás, B., Mike, A., Sipos, E., Arszovszki, A., Brunner, J., Szatai, Á., Yaseen, F., Andrási, T., Szabadics, J., 2025. Optical Recordings of Unitary Synaptic Connections Reveal High and Random Local Connectivity between CA3 Pyramidal Cells. J. Neurosci. 45, e0102252025. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0102-25.2025

Lin, A., Yang, R., Dorkenwald, S., Matsliah, A., Sterling, A.R., Schlegel, P., Yu, S., McKellar, C.E., Costa, M., Eichler, K., Bates, A.S., Eckstein, N., Funke, J., Jefferis, G.S.X.E., Murthy, M., 2024. Network statistics of the whole-brain connectome of Drosophila. Nature 634, 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07968-y

Marx, V., 2025. Method of the Year: EM connectomics. Nat Methods 22, 2470–2475. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02906-w

Matsliah, A., et al., 2024. Neuronal parts list and wiring diagram for a visual system. Nature 634, 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07981-1

Scheffer, L.K., et al., 2020. A connectome and analysis of the adult Drosophila central brain. eLife 9, e57443. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57443

Schlegel, P., et al., 2024. Whole-brain annotation and multi-connectome cell typing of Drosophila. Nature 634, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07686-5

Schmidt, M., Motta, A., Sievers, M., Helmstaedter, M., 2024. RoboEM: automated 3D flight tracing for synaptic-resolution connectomics. Nat Methods 21, 908–913. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02226-5

Sievers, M., Motta, A., Schmidt, M., Yener, Y., Loomba, S., Song, K., Bruett, J., Helmstaedter, M., 2024. Connectomic reconstruction of a cortical column. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.22.586254

Tavakoli, M.R., Lyudchik, J., Januszewski, M., Vistunou, V., Agudelo Dueñas, N., Vorlaufer, J., Sommer, C., Kreuzinger, C., Oliveira, B., Cenameri, A., Novarino, G., Jain, V., Danzl, J.G., 2025. Light-microscopy-based connectomic reconstruction of mammalian brain tissue. Nature 642, 398–410. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08985-1

Pingback: Annual report of my intuition about the brain (2025, part II) | A blog about neurophysiology

Pingback: Annual report of my intuition about the brain (2025, part III) | A blog about neurophysiology

Thanks for writing this piece. I found the discussion of technical challenges helpful. I wanted to ask a clarifying question about the “Why it won’t work” section.

Is your claim that:

(a) We can’t currently reconstruct memories/mind from a preserved connectome with today’s technology, or

(b) A well-preserved connectome would never allow for reconstructing the memories/mind of a preserved animal, even with future technology that might be developed in the next 100-200 years?

These seem like very different claims. It seems to me like your arguments about imaging scale, data analysis bottlenecks, and open questions about the need for biomolecular annotation all seem to support (a). But the way you framed the section suggests (b).

The reason I ask is because it matters for evaluating brain preservation efforts like those advanced by the Brain Preservation Foundation. The argument is not “we can revive people today” but rather “there is some reasonable probability that current preservation methods capture enough information for future technology to work with.” And of course this all assumes high-quality preservation in the first place.

If your claim is (b), I’d be curious what you see as the fundamental barrier(s) rather than a gap in current engineering or knowledge that could eventually be closed.

As an aside, my sense is that most people in this space are genuinely uncertain about whether the electron microscopy-visualizable connectome alone would be sufficient to reconstruct memories, or whether additional approaches — like expansion microscopy with molecular annotation of key biomolecules — might be required. I personally lean towards the latter, but I’m also aware that it might be possible to infer a lot of the biomolecular content from ultrastructural features alone.

– Andy McKenzie (amckenzie@apexneuro.org)

Hi Andy, you’re right that I was mixing these two concerns that are fundamentally distinct from the perspective of brain preservation efforts.

For the next decades, in my opinion the main limitation will be point (a), the technical limitations of EM-based connectomics.

But I also believe (b) that connectomics based on EM reconstructions will not be sufficient to revive dead brains. A synapse is a complex compartment with a plastic distribution of ion channels, organelles and other proteins involved in signal transmission and plasticity, and we have no handle on these details when we perform high-resolution EM. And I don’t see any possibility to identify e.g. the distribution of a number of ion channels or their molecular configurations from electron microscopy. Why is this important? Because in order to revive a dead brain in silico, we will probably need these details to simulate the reconstructed neurons. If we don’t do this, synapses will behave differently, the integration time constants of the neuron will be off, and signals inside of the dendrites and axons will be conducted in a way and with a speed that is different from the original neuron of the human brain; therefore, the simulation will be very different from the true neuron. It is as if all transistors and capacitors in a computer are wrongly specified: it would be a complete mess. I write “probably”, because there is a chance that this simulation will not require any of those details. I would personally consider this chance very low. But I can see that others have different opinions on that. We will only know in the far future. There are currently many exciting efforts to use simplified models based on connectomes in order to understand the computations performed by these circuits, and the outcomes are promising and very interesting (although the goal is rather to extract principles of neural circuits, not specific memories and brain states).

You also bring up expansion microscopy together with molecular annotation. This is currently an emerging field and not as mature as EM-based connectomics, so it remains to be seen what the limitations of this approach are. But I agree with you that this additional information about biomolecular distributions at high resolution might resolve some of the limitations of EM-based connectomics, (at least in theory). So, from the perspective of a brain preservation person, there is definitely room for hope for such future technology to reconstruct and revive brains in 100-200 years (although one can argue whether this preservation effort is justified).

On a note related to expansion microscopy, I have recently been working on a method for clearing of fixated human brains, which would, with minor modifications, also be compatible with expansion microscopy (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.05.21.655358v1). It is pretty amazing to see 15-year-old brain samples deparaffinated again and labeled with antibodies – but your application would go three steps further: higher resolution by expansion, full brain instead of centimeter-sized tissue blocks, and multiple rounds of antibodies. None of this is easy, but it may be possible.