Astrocytes are brain cells that are often completely overlooked and dismissed or, in the opposite extreme, presented as mysterious devices that somehow solve all problems of computational neuroscience. The truth is somewhere in the middle, but it is not clear yet where exactly. First of all, we still do not understand even the basic mechanistic rules by which individual astrocytes operate. For neurons, we have precise, often even mathematical ideas how they receive input via synapses, how they depolarize, and how depolarizations propagate to the soma and elicit action potentials. For astrocytes, this mechanistic book of rules is still missing – and this gap limits our ability to interpret experiments or build coherent theories.

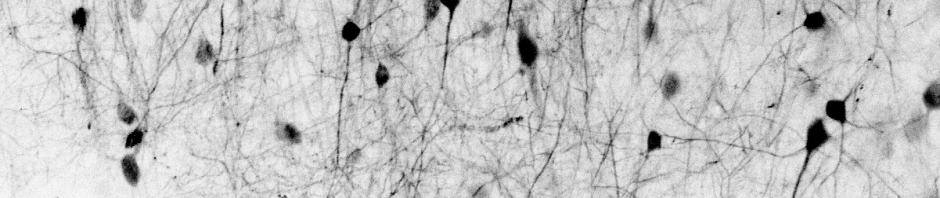

As part of the effort to close this gap, some of my own research focuses on how astrocytes respond to neuromodulatory input and how they process these responses through subcellular calcium signals (Rupprecht et al., 2024). These signals depend not only on passive propagation – somewhat analogous to passive dendritic spread in neurons – but also on the fine astrocytic morphology (branches, branchlets, leaflets/perisynaptic astrocytic processes, and endfeet) and on the subcellular organelles (endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria) that shape calcium dynamics.

Below, I highlight a few recent studies that may advance our understanding of astrocytic structure and function, and illustrate both how far we have come and how far we still need to go.

Synapses are partially wrapped by astrocytic processes

A central concept in astrocyte biology is the “tripartite synapse”. This describes the idea that a neuronal synapse, consisting of a presynapse and a postsynapse, is wrapped by a third component (hence the “tri”), an astrocytic process, creating a microenvironment where the astrocytic process interacts with the synaptic partner for neuronal plasticity, neurotransmitter clearance and maybe other purposes. However, it was not clear how much of the synaptic landscape is actually “covered” by astrocytic processes.

A recent study by Nam et al. (2025) reported that over 85% of synapses in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus have an astrocytic process within 120 nm of some part of the synaptic perimeter. This study comes from the Harris lab, which is worth mentioning since Kristen Harris was one of the key researchers to establish the concept of the tripartite synapse (Ventura and Harris, 1999). Another recent study by Yener et al. (2025) from the Helmstaedter lab examined synaptic coverage in mouse somatosensory cortex. This is how the 3D reconstruction of a tripartite synapse looks like (taken from Figure 1 of Yener et al. (2025), under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license):

Using a stringent criterion (“≥50% of synaptic perimeter covered by astrocytic membrane within 40 nm”), they found that only ~23% of synapses were wrapped by PAPs. At first glance, this seems surprisingly low, first compared to the concept of tripartite synapses, and second compared to the study by Nam et al. (2025), who reported much higher coverages.

But when we look more closely, we can see that this number heavily depends on the definition of “wrapping.” When the authors relaxed the distance and coverage criteria (e.g., 20% coverage within 100 nm), the proportion increased dramatically – up to ~78%, which would be again more consistent with the study by Nam et al. (2025). Yener et al. (2025) also provide this nice plot below to make these relationships transparent (taken from Figure 1 of Yener et al. (2025), under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license):

Therefore, the datasets are relatively consistent; what differs is how authors interpret which distances and coverage percentages are biologically meaningful – and this is an important point. Structural metrics are only interpretable in the context of hypotheses about how astrocytes interact with synapses and what temporal precision is required for that interaction.

On that note, it is interesting to see that both Yener et al. (2025) and Nam et al. (2025) relate their structural findings to synaptic plasticity. However, they use very different methods to infer or generate synaptic plasticity – using LTP and LTD protocols in slices by Nam et al. (2025), and co-variances of spine sizes by Yener et al. (2025), a method that was – interesting coincidence – partially established by Bartol et al. (2015), which was a collaboration where Kristen Harris’ lab contributed the experimental part. Back to Yener et al. (2025) and Nam et al. (2025): The results from the two approaches about synaptic coverage as a function of LTD vs. LTP are, unfortunately, not really consistent, and there are too many possible reasons for the differences to be worth discussing. It will in any case require additional future work to get a clear picture.

Multiple astrocytic processes combine to wrap multiple synapses

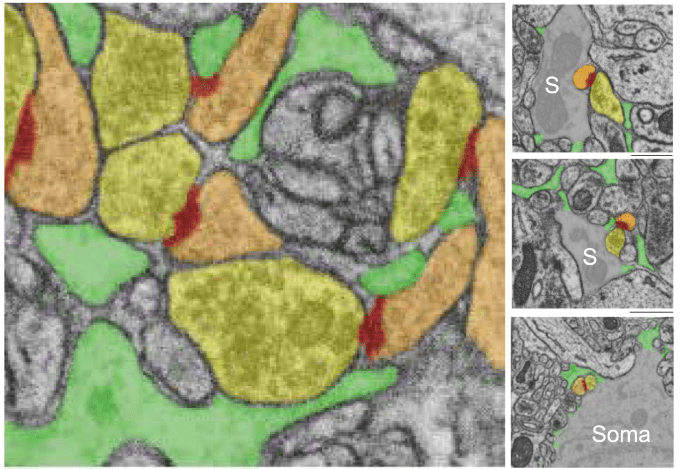

A study that challenges our textbook view of astrocyte-synapse interactions is by Benoit et al. (2025) from the labs of Karin Pernet-Gallay and Andrea Volterra. This study directly questions the concept of the “tripartite synapse” – where the idea is that a functional unit is formed by one presynaptic terminal, one postsynaptic terminal, and one astrocytic process wrapping around.

Astrocytes form small processes (10-20 nm) that are called “leaflets” or, when wrapping around neuronal synapses, “perisynaptic astrocytic processes (PAPs)”. These astrocytic processes are too small to be resolved by light microscopy but can be identified by electron microscopy. Benoit et al. use large-volume electron microscopy to demonstrate that the smallest astrocytic processes (leaflets/PAPs) do not primarily wrap individual synapses but instead form multi-leaflet networks that, connected via gap junctions, ensheath groups of 1–20 synapses. This is a very interesting finding that might change how we think about ensembles of synapses and how they may be controlled as a group of synapses by mediation of this shared ensheathing by a common leaflet, forming – as the authors put it – a “tripartite synaptic network”. Here is an example from their paper which nicely illustrates the idea – even though the choice of colors is one of the worst I have ever seen for color-blind people like me, with leaflets in green, axonal boutons in yellow, spine in orange and synaptic cleft in red (from Figure 2 of Benoit et al., 2025, under the CC BY 4.0 license):

With their analysis, they also add a data point to the question of “astrocytic coverage” discussed above. Consistent with the interpretation of Yener et al. (2025), they find low coverage of synapses by individual leaflets – however, they find that the majority of synapses receives a larger “astrocytic coverage” by a larger ensheathing by multiple leaflets.

Benoit et al. (2025) go one step further, attempting to image functional signals in leaflets vs. calcium signals in other processes of astrocytes. Because leaflets are too small to resolve with standard in vivo imaging, the authors used a creative indirect approach. Since mitochondria are absent from leaflets but present in larger astrocytic processes, they image mitochondrial markers in a secondary channel and can thus infer which calcium signals originated from leaflet vs. non-leaflet regions. This approach, of course, cannot deliver the same precision as electron microscopy, but is a very interesting tool to functionally dissect subcellular structures in astrocytes. For more details, check out the paper – it is worth it.

Astrocytes as mediators of neuromodulatory feedback

A final recent study I would like to mention is by Xin et al. (2025) from the lab of Hailan Hu. It is not about ultrastructural properties but about the function of astrocytes in brain-wide circuits. Hailan Hu’s lab is well-known for their expertise on the lateral habenula and its role in depression. Here, they pull off an impressive array of experiments (fiber photometry, pharmacological and genetic perturbations of cell types or signaling pathways, behavior, etc.) that could have easily been several distinct and interesting papers.

Their main observation is that the lateral habenula (LHb) is activated (based on fiber photometry) before many other brain regions during stress. This activity in turn switches on the locus coeruleus (LC), which is known to project to a large part of the brain including cortex and hippocampus – where I have studied its long-range effects on astrocytes (Rupprecht et al., 2024), and where slice work indicates that these activated astrocytes release ATP/adenosine and thereby inhibit neurons in CA1 (Lefton et al., 2025). But LC also projects back to LHb, where it also activates astrocytes. Interestingly, Xin et al. (2025) observe that these astrocytes not only release adenosine but also glutamate, which results in a net activation of LHb neurons in a second wave. This claim is, however, not as solidly supported by the data as it appears at first glance: In Figure 4k (which I cannot show here due to copyright restrictions), Xin et al. (2025) test multiple antagonists against glutamate receptors, adenosine receptors, GABA receptors, etc. They see a small reduction after superfusing the antagonist, which is, however, only significant for glutamate, ATP-R and A2AR antagonists. Each of those experiments is done with 2-3 slices, but they perform statistics based on single cells. Of course, one would expect batch effects between slices, and the actual power of the experiment is much lower than reported. This is a common fallacy that can be seen in most papers. The proper way to deal with this statistical problem would be to use hierarchical statistics, for example based on linear mixed-effect models.

Despite these minor concers, I still find it a very interesting study, full of many advanced technical approaches. Personally, I would have preferred to go in much more depth for individual experiments with more detailed analyses. As they are, many results are only minimally discussed (due to space constraints). They nicely act as puzzle pieces within the bigger story. But they are not dicussed – and with “discussed”, I mean “analyzed” – beyond this limited horizon of interest. To give an example, Xin et al. (2025) use complex behaviors such as foot shocks to elicit stress responses; but it would have been interesting to simultaneously monitor motor and other behavior to better relate the temporal components of the neuronal responses to what is going on with the animal. But I can understand why it also makes sense to condense this massive amount of diverse experiments into a single paper in order to highlight the story and the main finding. In any case, if you work on astrocytes or locus coeruleus, this is a must-read.

References

Bartol, T.M., Bromer, C., Kinney, J., Chirillo, M.A., Bourne, J.N., Harris, K.M., Sejnowski, T.J., 2015. Nanoconnectomic upper bound on the variability of synaptic plasticity. eLife 4, e10778. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.10778

Benoit, L., Hristovska, I., Liaudet, N., Jouneau, P.-H., Fertin, A., De Ceglia, R., Litvin, D.G., Di Castro, M.A., Jevtic, M., Zalachoras, I., Kikuchi, T., Telley, L., Bergami, M., Usson, Y., Hisatsune, C., Mikoshiba, K., Pernet-Gallay, K., Volterra, A., 2025. Astrocytes functionally integrate multiple synapses via specialized leaflet domains. Cell 188, 6453-6472.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.08.036

Lefton, K.B., Wu, Y., Dai, Y., Okuda, T., Zhang, Y., Yen, A., Rurak, G.M., Walsh, S., Manno, R., Myagmar, B.-E., Dougherty, J.D., Samineni, V.K., Simpson, P.C., Papouin, T., 2025. Norepinephrine signals through astrocytes to modulate synapses. Science 388, 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq5480

Nam, A.J., Kuwajima, M., Parker, P.H., Bowden, J.B., Abraham, W.C., Harris, K.M., 2025. Perisynaptic Astroglial Response to In Vivo Long-Term Potentiation and Concurrent Long-Term Depression in the Hippocampal Dentate Gyrus. J. Neurosci. 45, e0943252025. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0943-25.2025

Rupprecht, P., Duss, S.N., Becker, D., Lewis, C.M., Bohacek, J., Helmchen, F., 2024. Centripetal integration of past events in hippocampal astrocytes regulated by locus coeruleus. Nat Neurosci 27, 927–939. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01612-8

Ventura, R., Harris, K.M., 1999. Three-Dimensional Relationships between Hippocampal Synapses and Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 19, 6897–6906. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06897.1999

Xin, Q., Wang, J., Zheng, J., Tan, Y., Jia, X., Ni, Z., Xu, Z., Feng, J., Wu, Z., Li, Y., Li, X.-M., Ma, H., Hu, H., 2025. Neuron-astrocyte coupling in lateral habenula mediates depressive-like behaviors. Cell 188, 3291-3309.e24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.04.010

Yener, Y., Motta, A., Helmstaedter, M., 2025. Connectomic analysis of astrocyte-synapse interactions in the cerebral cortex. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.20.639274