Ardem Patapoutian is a neuroscientist who works on the molecular basis of sensation via mechanosensitive ion channels. In 2021, he was one of the recipients of the Nobel prize, at a relatively young age. He has since used his influence among scientists to speak out for improving academia for both research and the humans who do the research.

In a post on Twitter, he compiled a list of 13 rules on how to do science. I strongly agreed with some aspects, disagreed with others (after all, Ardem is a scientist in a slightly different field), and felt inspired to share some thoughts about his list. I’m writing these comments also because I’m curious what I will think about my current ideas in 10 or 20 years from now. Here’s the list:

1. Don’t be too busy (Rule #1: No excuses. If you’re too busy, you’re not being creative).

I’d subscribe to this statement 100%.

As a PhD student, I had only few fixed responsibilities. Every couple of months, I started a new side-project, learned a completely new experimental technique, a new programming language, read about a new field of computational neuroscience, etc. 7 years ago, I gave an interview about this creative process for my science. I believe that these deep dives into unknown territory are necessary for creativity. Creativity is often a combination of two influences from two different fields; in the simplest case, it’s just the application of a certain domain to another – let’s say, the use of a fancy cooking technique for the improvement of an immunohistochemistry method. Such a knowledge transfer requires not only focused work on the target method (immunohistochemistry), but also a deep knowledge about the other field (fancy cooking), which requires time, an exploratory spirit – and an appreciation for the fact that time spent understanding one domian can always be beneficial for another domain.

I noticed for myself that the available time that I have for such digressions became less once I became a PI, and it will become worse over time in the future. But I hope to maintain conditions in the future that won’t prevent me from staying creative!

2. Learn to say no (related to #1).

That’s a very commonly given advice, but few people seem to follow it. “Saying no” is not only about focusing on one’s own projects and tasks, but also about saying no to the inner voices and the peer pressure. You need to publish in Nature. No, you don’t; don’t lose yourself while trying. You need to finish your PhD with 30. No, everybody at their own pace! You need to have >3 PhD students. No, one may be just enough for some situations. You need to become a professor within 5 years. No, you don’t. Life outside academia has many things to offer.

For some people, learning “no” only seems applicable to requests from other people. But learning to say “no” to the internal voices – which are often only the internalized voices of other people, be it peers, parents or professors – can be even more important to free the mental resources for doing creative work and for doing real science.

3. What question to ask: Find the biggest unanswered question that can be approached in the next 5-10 years.

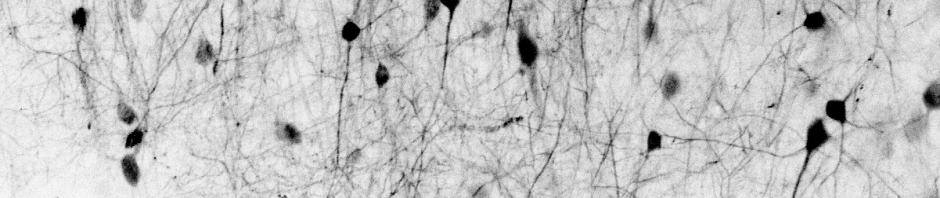

I don’t fully agree with that one for my field of science. In basic systems neuroscience, the relevant question is “how does the brain work”, and it cannot be approached within 5-10 years. In the meantime, from my own perspective, it seems to make more sense to find small islands of mechnistic understanding and curious observations (for example, I could pick behavioral timescale synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons or centripetal integration in astrocytes as starting point phenomena) and continue to work from there bit by bit, even though it’s not yet clear how these questions can be answered within 10 years.

4. Science communication: When you talk about your work, always start by stating what the important open question is (this is fundamental, but very few do it; related to #3).

That’s good advice! I should do that more often.

5. Prioritize: Know when to quit a project (as important as coming up with new ideas).

Very good advice again.

I think it is very beneficial to invest a lot of energy trying to kill a project as early as possible. For example, trying to find a critical flaw in a conceptual idea before implementing it in a tedious series of experiments, and then realizing that the data cannot be analyzed properly.

For example, a typical situation at the beginning of an experimental systems neuroscience project is the design of a behavioral task for an animal. Will it be possible to extract the desired mental states from the acquired data, or will these states be confounded by movement or arousal of the animal? These are questions that need to be considered before, not after the experiment.

It happened to me already 3 times that I stopped my main scientific project (1x during my PhD, 1x during my postdoc, 1x as junior PI) because I convinced myself by theoretical arguments or by some analyses that it would not work out. And it happens much more often for smaller project.

6. Change fields when the open questions are no longer interesting: Being from a different field allows you to look at problems with a fresh perspective.

I’m very skeptical about this piece of advice. Maybe I’ll think differently in 20 years. But at the moment, I have the impression that those who stay in a field and try to figure out the little details are my real scientific heros. If you’ve found a real effect, you should go for it fully and not drop it for the newest hot stuff. Otherwise, one risks joining a new field where the open questions only seem interesting from outside, the typical “hype train”.

7. Ask for help – don’t reinvent the wheel.

As somebody who built several microscopes and data analysis pipelines from scratch, I can agree only very reluctantly. I learnt so much from reinventing these wheels! And I would be a much worse scientist without.

I still remember my first year of physics studies, when I did not know of any sort of theoretical neuroscience. Back then, I tried to develop a weird form of math that can deal with neuronal connectivity and dynamics. Only a year later or two, I stumbled across Dayan & Abbott’s famous Theoretical Neuroscience and learned that matrix algebra is a great and existing tool for that. But I still wonder what kind of math I would have come up with if I’d been more gifted for it and if I’d had more time without Dayan & Abbott.

However, I also noticed that several extremely skilled scientist-tinkerers like Jakob Voigt and Spencer Smith (I was unable to find his blog post on this topic) turned into advocates of professional infrastructures later during their careers, advocating against the repeated reinvention wheels.

I still cannot decide whether the established black box button-press infractructure are more error-prone, or the code written from scratch by a very smart PhD student. From the perspective of a PhD student, it is probably better to write and build everything from scratch, because you learn more and know what is going on. From the perspective of the PhD student’s supervisor, however, it is better if an existing and tested infrastructure is used, because otherwise there is no efficient way to make sure that the results obtained by the PhD student are valid. Maybe these two different perspective are also the reason why some people change their mind once they are professors.

8. Don’t listen to advice if it doesn’t make sense to you (this does not contradict #7).

No strong opinion on that.

9. Hire people who are smart, efficient, and kind (don’t forget about “kind”).

Agree. Even more important: As a PhD student, join a lab with a smart, efficient and kind PI (don’t forget about “kind”).

10. Champion the underprivileged.

Agree.

11. Collaborate with people with very different training and experience.

I have a hard time agreeing with this rule. My best collaborations have been with people who were technically stronger than me. Collaborations with people who have only limited understanding and, in particular, limited appreciation for the skills that I bring into a collaboration, can be quite painful. But maybe I will judge collaborations from an entirely new angle in 10 years.

12. Cultivate friends who tell you when you are wrong.

I noticed that senior PIs often do not have anybody (not a single person!) who tells them with all honesty when they are wrong. If such a condition is combined with a narcisstic personality of the senior PI, things can become really bad and embarrasing. I do not yet know how exactly to prevent this from happening, because it seems to happen to the best scientists, and it seems particulary common for men (less so for women according to my observations).

13. Don’t forget why you got into this business in the first place: Science is fun. Minimize the noise that causes anxiety.

I also think that reduction of anxiety is indeed important (related to #1 and #2). But I don’t have a recipe on how to reach such a state. From my own and very limited experience as an observer, the level of anxiety seems to be relatively stable for a given person within academia, independent of the position. I happen to be one of those persons who are not very anxious in general. The reason for this lack of anxiety is maybe that I’m not afraid of leaving academia, because I’m sure I would find another interesting job as well, and because my family does not have any ties with academia. But first of all, it’s probably a personality trait which I owe primarily to my genes and to my parents – and I’m grateful for that!